IT 25 · 50 Symposium (LIVE 2:41:36)

Alan Kay Keynote (with Japanese subtitles 42:57)

IT25・50 Symposium Live

December 10, 2018

Why We Need To Understand What Douglas Engelbart Was Trying To Do

Alan Kay

Viewpoints Research Institute

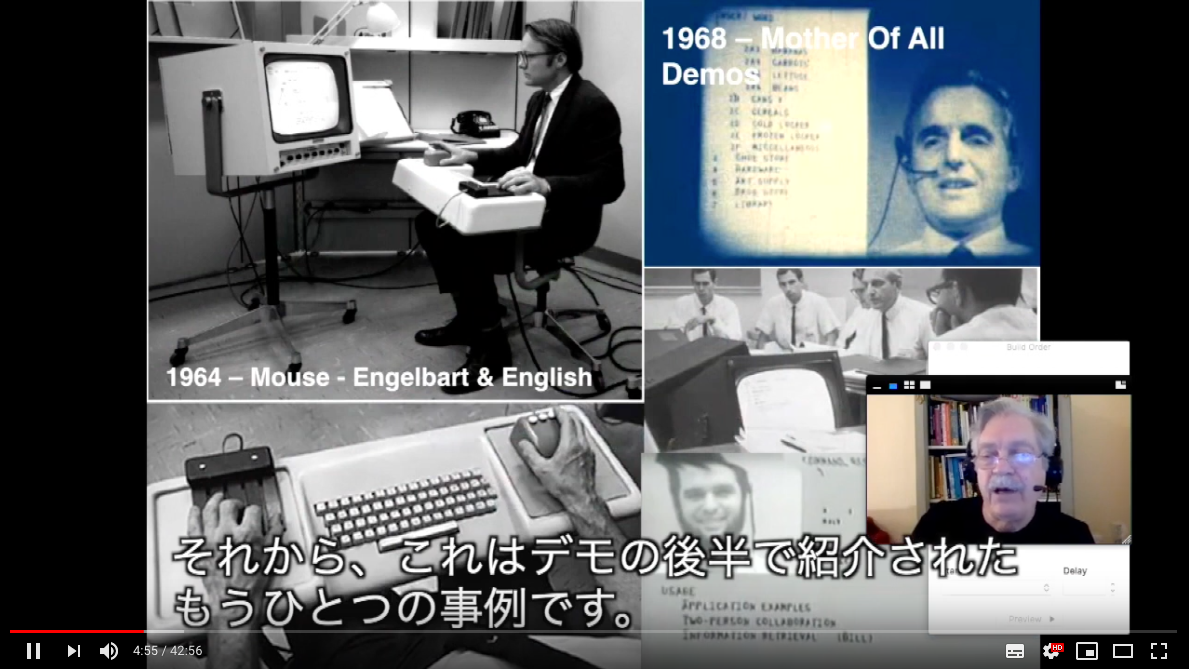

It was one of those, was one of those years where many things happened and one of them was the big demo where we–the mouse was first shown to most of the world. And many other things, but the very same year was the first great pen-based system called Grail and the first great pen-based pointing device. And also, and I think at the very same conference, the first great virtual reality system was shown in 1968.

50年前、1968年はパーソナルコンピュータの誕生にとって記憶すべき年でした。多くの出来事がありましたが、そのひとつがダグ・エンゲルバートのビッグ・デモでした。そこで初めてマウスが一般に向けて披露されたのです。

同じ年には、GRAILという最初のペンベースのシステム、そして最初のペンベースのポインティング・デバイスも生まれました。素晴らしき最初のヴァーチャル・リアリティのシステムも確か同じ会議で発表されたはずです。

And as was mentioned earlier, this idea of a personal, very mobile tablet sized computer for everybody, but especially to include children. So, the idea is to have it be as much like a book that you learn in childhood as an automobile you might learn later in life.

紹介にあったように、私が、あらゆる人たち、特に子供を対象にしたタブレット型のパーソナル・モバイル・コンピュータのアイデア「ダイナブック」を最初に発表したのも1968年でした。それは、子どもたちが持ち運んで学習に使える本のようなものであり、かつ、将来、大人になれば、誰もが車を実際に運転しながら学ぶように、子供のうちから実際に体験しながら学べるものを考えたのでした。

But I’m going to concentrate on the Engelbart ideas and the big demo and also why we need to understand what Engelbart was trying to do because as we’ll see, the concentration on the technology on the mouse and the video conferencing and so forth, kind of got in the way of people understanding what the bigger ideas that Doug was doing.

ただ、今日はエンゲルバートのアイデアとビッグ・デモに集中したいと思います。そして、エンゲルバートが何をしようとしていたかを理解する必要があることをお話したいと思います。なぜなら、我々はついマウスやビデオ会議機能などテクノロジーのことに目が行きがちですが、これらはかえって、人々がより大きなアイデアが何であったかを理解する妨げとなっているからです。

Here’s the hall where the demo was done; about 2000 people fit in it. Here’s where I sat to watch the thing. And you can see the screen is enormous, but there’s a video projector that cost about a million and a half dollars that could show this.So, that was what things looked like during this demo and they showed many things.

ここが、デモが行われたホールです。2,000人くらい収容できるホールでした。私が座っていた位置はここでした。ご覧のようにスクリーンはとても巨大で、150万ドルくらいするプロジェクタがありました。

デモの時は、舞台はこのように見えていました。このデモでは数多くのものが紹介されました。

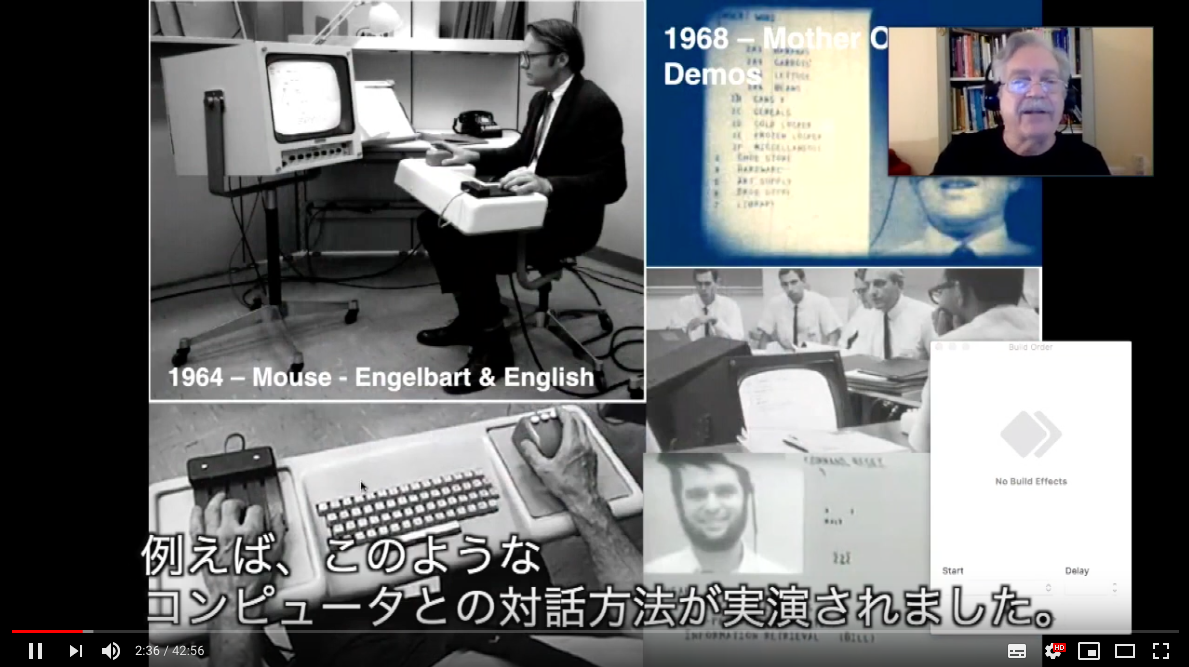

They had this way of interacting as you can see, that was a little nicer than what we have today because it allowed you to keep your hands on the navigation device, which was the mouse here. And also, there was this key set that allowed you to, in combination just fly through this information space at very high rates of speed. The regular keyboard in the middle was used for typing lots of texts but you didn’t need it for typing small amounts of text. So, this is a very efficient interface. And here are–I’m just going to show you a couple of things from that demo to give, to give you an idea.

例えば、このようなコンピュータとの対話方法が実演されました。これは今よりもちょっと便利だったと言えるでしょう。なぜなら、指示装置としてのマウスから手を離す必要がなかったからです。このキーセットを使って、複数のキーの組み合わせを同時入力することにより、情報空間を非常に速い速度でまわることができました。真ん中には普通のキーボードがあり、大量のテキストを入力する時に使えるのですが、ちょっとしたテキストの入力であれば、キーボードを使う必要がなかったのでとても効率的だったのです。ここでデモの内容をちょっとだけ紹介してみます。

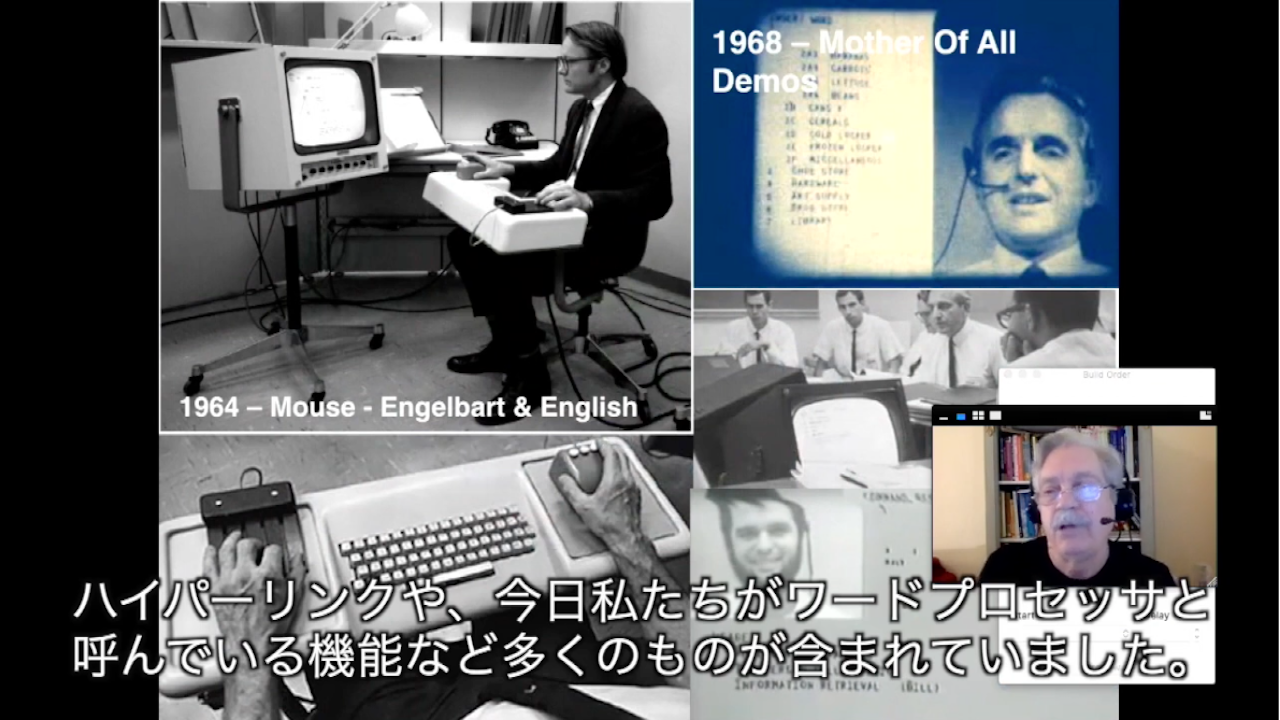

There are many, many things there including hyperlinking and what we call word processing today and so forth.The problem with looking at this today is the system was quite a bit more capable than most of the systems we use today. The only thing that wasn’t as capable was how good the display looked.

ハイパーリンクや、今日私たちがワードプロセッサと呼んでいる機能など、多くのものが含まれていました。今見ても、このシステムには、今私たちが使っているシステムより優れているところがありました。ただ、ディスプレイの質は今より劣っていました。

Here’s another example later in the demo.

So, that looks like what we’re doing right now except consider this. Actually, I’ll say this in a little bit. Here’s the last thing is that when they had meetings, they had the meetings using this system as a shared blackboard. Because, not only could you share with one person, you could share with a lot of people. And everybody had their own little pointer on the screen. So, this was not like Google Hangouts where you have to fight over the pointer. Your hand was extended into this shared system.

それから、これはデモの後半で紹介されたもうひとつの事例です。現在私たちがやっているのと同じようなテレビ会議ですが、違うところがあります。ミーティング機能の最後のところですが、共有黒板を使っているのです。つまり、大勢の参加者で共有でき、参加者それぞれが誰もがポインタを持っていたわけです。グーグル・ハングアウトと違って、参加者はポインタを取り合わなくてもよいのです。自分の手が、この共有システムの中に延長しているかのようでした。

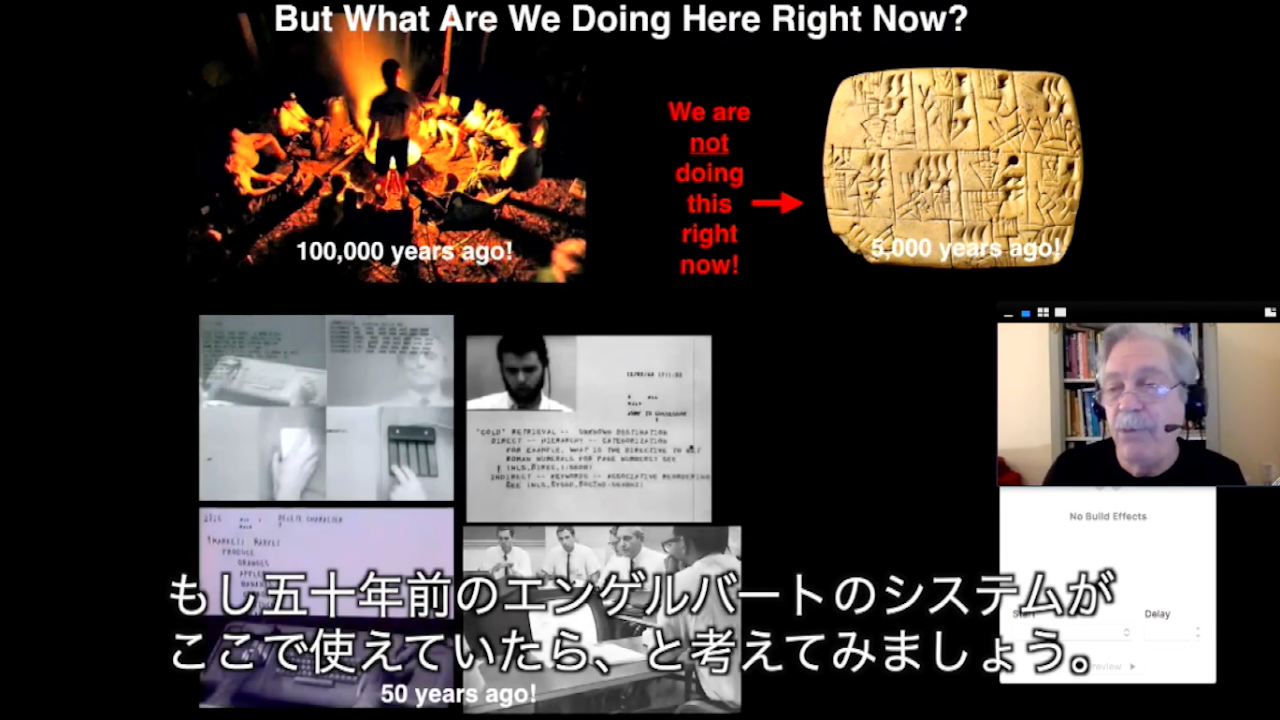

Well we’re not doing any of this. We’re actually doing something that would be quite familiar one hundred thousand years ago to cave people. And you came–even though I’m doing this from London–for some reason you came to this room that you’re sitting in. And I am beaming in. But basically, I’m–you’re sitting around a campfire and I’m telling you a story. So, this is something that would be completely recognizable to everybody.

これをみると、私たちは今一体何をしているのだろうかと自問しなければなりません。私たちはここで示されたようなことを何もしていないのです。

私たちが今何をやっているのは、10万年前の洞窟に住んでいた人たちにとっても馴染みのある風景でしょう。私はロンドンに居るわけですが、皆さんはそちらの部屋にいて、私が電送されて飛び込んできたというところでしょうか。基本的にはみなさんはキャンプファイヤーを囲んで座っていて、そこで私がストーリーを披露しているわけです。つまり、そのような穴居人であれ、ぱっと見ただけで何が起こっているのかわかるくらいのことであるということですね。

Now about five thousand years ago, this relatively recent technology called writing was invented. And it happens that writing is much more suited to what I’m going to try and explain to you. Why? Because you can read it at your own pace. You can go forward and back as you choose. And if you don’t understand something, you can check it out. You can’t do this right now because I’m just talking and talking and talking and so forth. And even if you go back and look at the video, it’s not as efficient for ideas as this stuff is. But we’re not doing that.

五千年前、書き言葉という比較的新しい技術が発明されました。実際のところ、書き言葉のほうが、私が説明しようとしている内容を説明するのにより適しています。なぜなら、皆さんは自分のペースで読みすすめることができるからです。好きな時に前後に行き来することもできますし、理解できないことがあれば、中断してそちらを調べることもできるわけです。しかし、今は私が延々話している以上、そういうことはできません。あとからビデオを見たとしても、この手のアイデアを説明するには効率はそれほどよくありません。

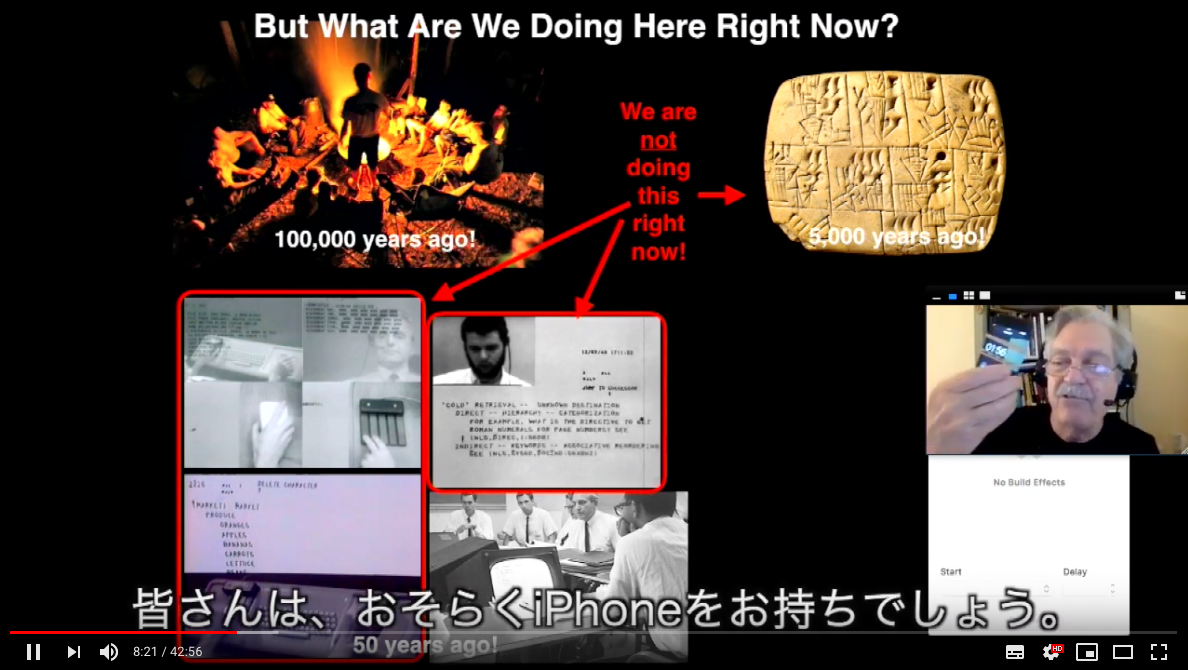

Well, we could be using something like the Engelbart system. In this case, from 50 years ago, you would be able to share, and I could manipulate stuff. Right now, I can’t pick up this text. I can’t do anything on the screen here because PowerPoint has walled off the system from me. It’s imitating transparent plastic that slides like we had 50 years ago. It’s not doing what a computer can do. So, this is crazy. So, we’re not doing that.

もし五十年前のエンゲルバートのシステムのようなものがここで使えていたら、と考えてみることができるかもしれません。みなさんの方から情報を共有することもでき、私がいろいろ操作することもできるでしょう。実際には、ここでこのテキストを動かすことさえできません。パワーポイントが、私からシステムを切り離してしまったからです。パワーポイントは、透明なプラスティック・スライド、すなわち50年前のOHPを模倣しているわけですが、これは馬鹿げたことです。コンピュータが可能にしたこともできていないのです。

All of you have iPhones. So, we could actually be sharing this presentation right now. And I could say, okay, go look in this and try this thing out. And you could be trying things while I’m talking. But the iPhone doesn’t allow that. And so, we’re not doing that. So, we’re not doing any of those things from 50 years ago. And what I want you to do is ask yourself what else could we be doing today.

Some of the underlying technology is much better than we had 50 years ago. So, one way of looking at this is writing is still in the future for most people. They learn it in school, but they don’t really use it. When it comes to discussing something, they don’t do it in writing. They come to a meeting.

The Engelbart system from 50 years ago, most of it is still in the future. You only think you have stuff like it, but you don’t. And then there’s stuff that Engelbart didn’t think about. So, almost everything about what I’m talking about here is still in the future. I’m just referencing this genius from the past.

皆さんは、おそらくiPhoneをお持ちでしょう。エンゲルバート・システムであれば、このプレゼンテーションを共有して、たとえば「これをご覧になってください」「これを試してください」といったら、プレゼンテーションを見ている間に試すことができるわけですが、iPhoneはそういったことを可能にしていないので、それができないのです。50年前からあるこれらのことができてない。このままでいいのかどうか自問してみてください。

現在では、いくつかの基礎技術は50年前よりはるかに改良されています。なぜこういうことになっているのかと考える方法の一つとして、ほとんどの人は、ものを書く段階に達していないのだろうと考えてみることができます。文章書きは学校で学んだはずですが、実質的には使えていないのです。そのため、何か議論をする際には、ものを書くのではなく、会議をしたがるわけです。

同様に、50年前のエンゲルバート・システムが提供していた機能も我々はまだそれを使える段階に達していないと言えます。いやもうそういう機能を使っていると思うかもしれませんが、実はそうではないのです。その上には、さらにエンゲルバートが考えなかったものが控えています。私がここで話しているのは、まだまだ将来のことです。ただ、この過去の天才を参考にしているわけです。

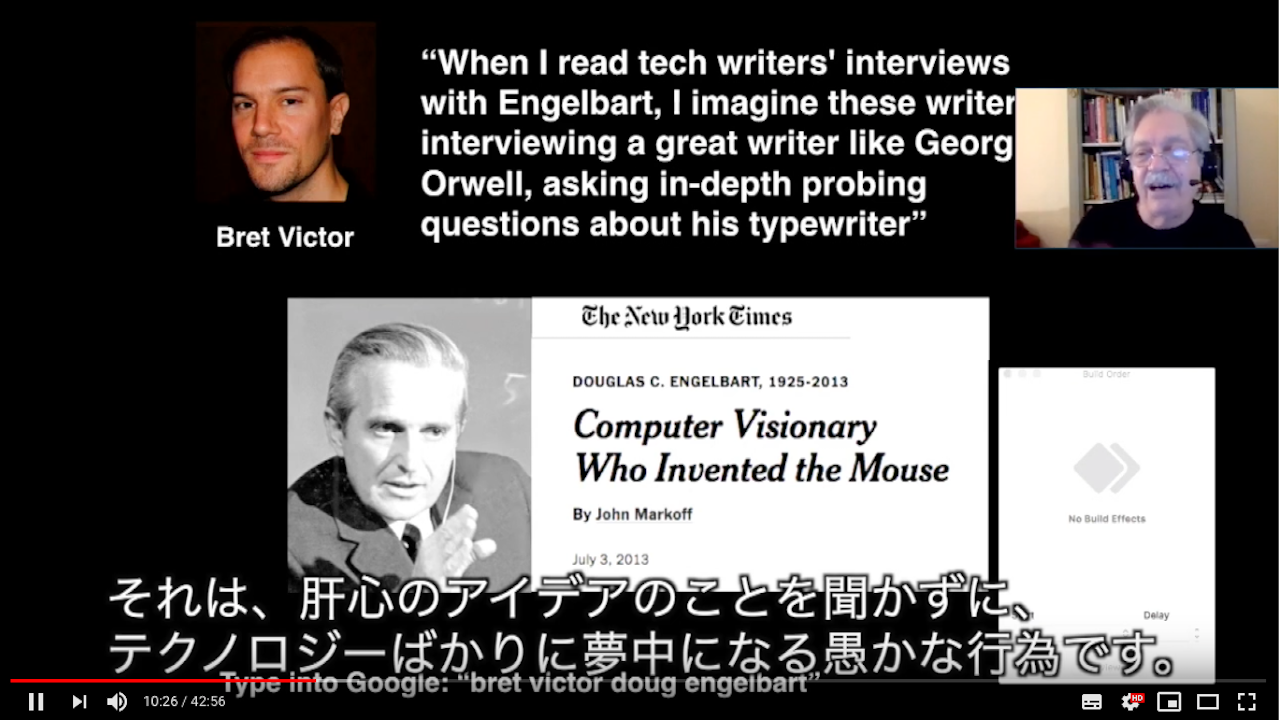

And my friend and colleague Brett Victor, who I think is the most brilliant young thinker about these things today said when Doug passed away, he imagined these writings about pieces in the newspaper about Doug which are all about the mouse and stuff, as being like journalists interviewing a great writer like George Orwell and only asking questions about Orwell’s typewriter. Forgetting to ask Orwell what he was thinking about and how did he do it and all that stuff. So, this is a kind of a stupid fascination with the technology and avoiding the ideas.

私の友人であり、かつ同僚のブレッド・ビクターという、若く優れた思想家がいます。彼は新聞のダグのインタビュー記事を読んで、「まるでジャーナリストがジョージ・オーウェルのような偉大な作家をインタビューする際に、オーウェルが使っているタイプライターの話を聞くばかりで、彼が何を考えていたのかとか、なぜそのようにしたのか、ということを聞かないようなものだ」と言っています。それは、肝心のアイデアのことを聞かずに、テクノロジーばかりに夢中になる愚かな行為です。

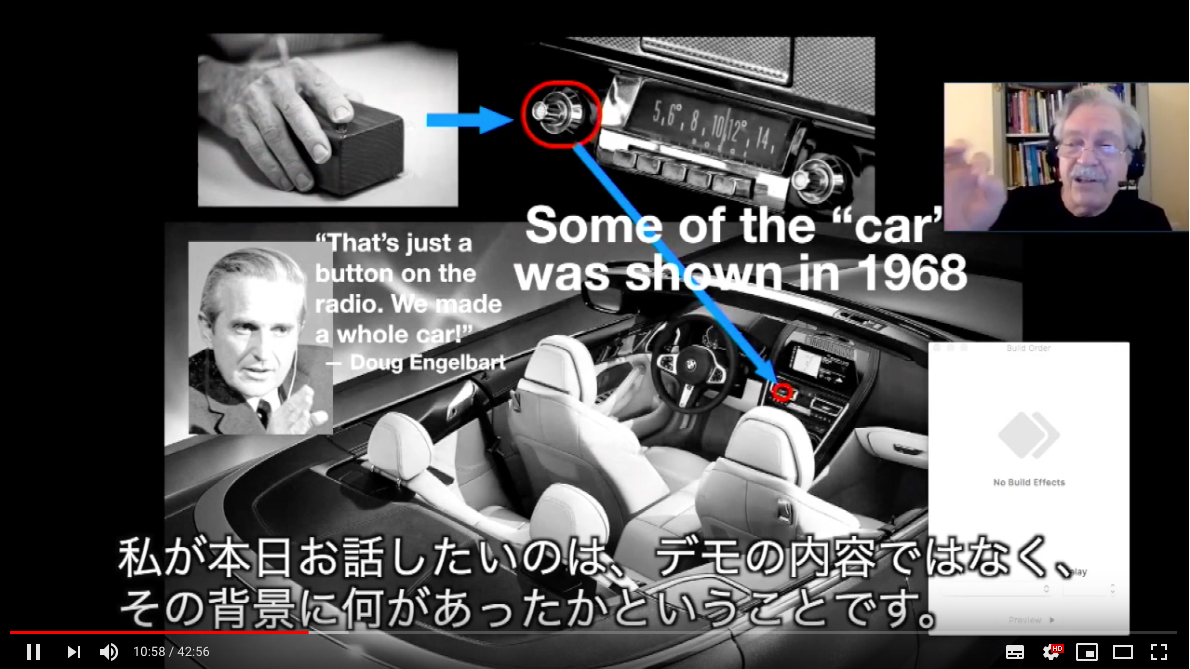

And this used to upset Doug. People always were talking about the mouse. And he said, hey, the mouse is just like a knob on the car radio and we made the whole car. We shared a whole car in 1968. The demo is 90 minutes long. Don’t worry about the mouse. Worry about the other stuff. They showed some of this. But what I want to talk to you about today is not the stuff that was in the demo but what was behind the demo. The demo has distracted from his really big ideas. Not about cars but about thinking vehicles for humanity. So, this larger idea, not a specific car. Not a plane, but the idea of vehicles. And the idea of thinking and what does that mean in the future.

そのことに、ダグ・エンゲルバートは非常に苛立ちを感じていました。みんなマウスのことばかり取り上げる。しかし、彼によれば、マウスはカーラジオのボタンみたいなものだ。マウスだけでなく、我々は車ごと作ったのだ、と言っています。このデモだけでも90分もあったのです。マウスのことは気にしないで、他のことをもっと考えてほしいと。私が本日お話したいのは、デモの内容ではなく、その背景に何があったかということです。

デモは、本当に大きなアイデアと関連しています。単なる一台の車についてとか、飛行機についてということではなく、人類のための移動手段という大きなアイデアです。考えるということはどういうことなのか、それは将来どういう意味を持つのかを考えることなのです。

And the reason for this is a lot of the things that people have said were invented and shown for the first time in this demo, not even close to historically.

So, the first interactive computer like the ones that we know about today, goes all the way back 17 years earlier to the early 50s with Whirlwind and MIT. And you can see there’s a display here and the first pointing device which is a thing like a gun you held in your hand called the Life Gun. And a few years later, this was turned into the Air Defense system with enormous computers, each with tens of people in the coordinating and working collaboratively. And this whole system actually became the Air Traffic Control system of the world. That’s what we use it for today.

このようなことを私が言っている理由は、人々がしばしば「このデモで初めて発表された」という、歴史的にまったく間違った意見を多くの発明について言っているからです。

今日の基準で対話型だといえる最初のコンピュータは、デモの17年も前に遡ります。1950年代の初め、MITのWhirlwindは、ディスプレイも最初のポインティング・デバイスも備えていました。それは銃のような形をしたもので、ライトガンと呼ばれていました。

数年後、これを元にした防空システムが生まれ出てきました。巨大なコンピュータが何台もあり、一台ごとに何十人ものスタッフがついていて、連携しながら作業していました。そして、今世界中で使われている航空制御システムとなっていったわけです。

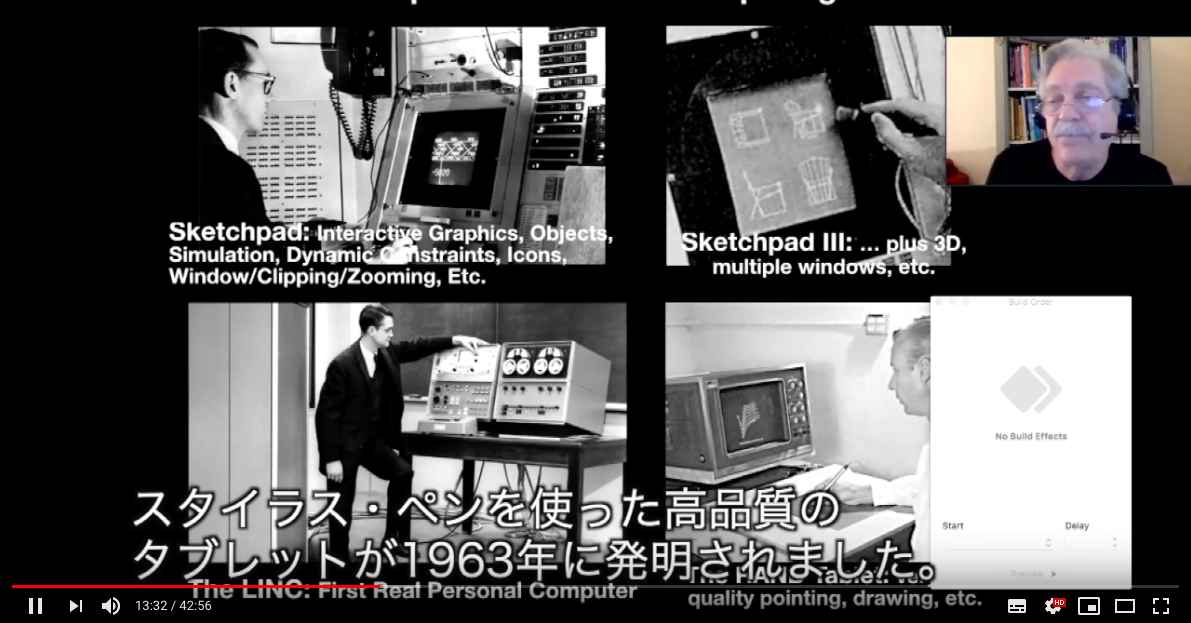

And also, in the early 60s was the, a system that already did some of the things that Doug had predicted earlier. So, this is the invention of interactive computer graphics, objects simulation–many things–icons, Windows, clipping, zooming, CAD, computer aided design, and so forth. And a year later was a 3D version of this with multiple windows. And the machine I think of as the first personal computer, which is called the Link, happened in 1962 also. And this super high quality stylus, thin-based tablet was invented in 1963 as well. So, there’s a lot of technology going on there.

そしてまた、1960年代初頭、ダグが以前に予測したことのいくつかを実現したシステムが作られました。このシステムを作るために、対話式のコンピュータ・グラフィックスなど、そしてオブジェクト、シミュレーション、アイコン、ウィンドウ、クリック、ズーム、CADなどの発明がなされたのです。一年後には、3次元データをマルチ・ウィンドウで扱えるものが作られました。

そして、私が最初のパーソナルコンピュータと考えている機械は、LINCというもので、これもまた1962年に作られました。それから、スタイラス・ペンを使った高品質のタブレットが1963年に発明されました。このように、多くのテクノロジーが同時に開発されていたのです。

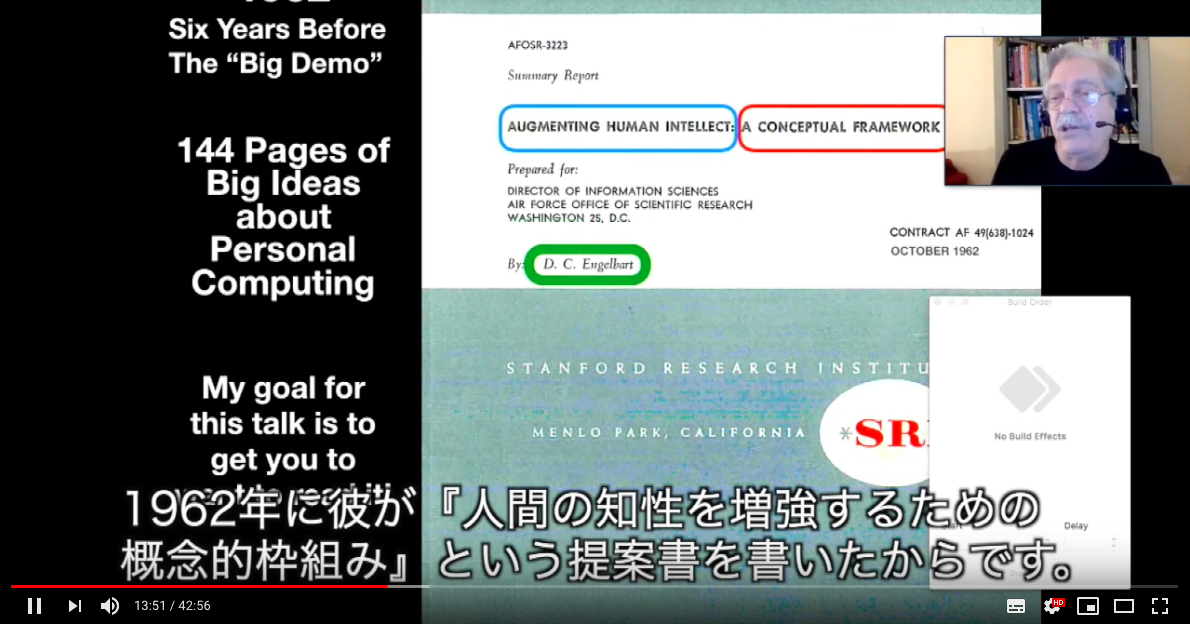

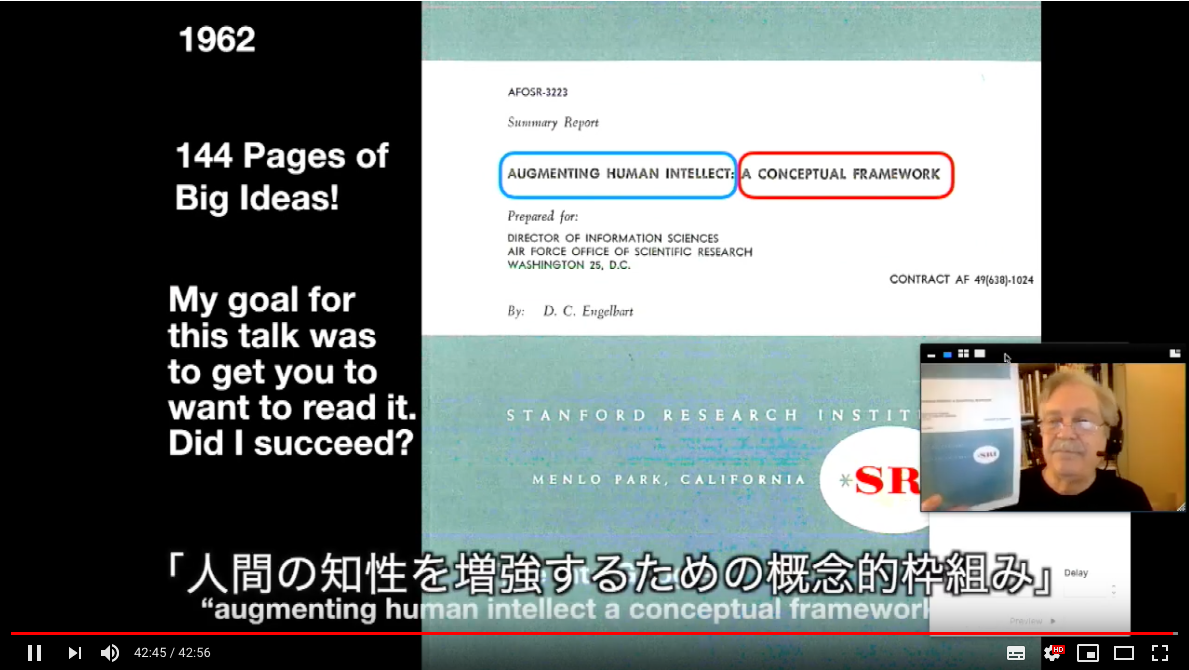

So, why are we talking about Engelbart? And the answer is that in 1962 he wrote this proposal called Augmenting Human Intellect, A Conceptual Framework. And it’s big. It’s 144 pages of ideas. Most people who are even interested in Engelbart have not taken the trouble to read this because they think that somehow watching the demo, they won’t have to. But in fact, this has many, many more ideas than they were able to do in the demo. And many more ideas than we still do today. So, my goal for this talk is to get you to read it. Here’s the–if you type Augmenting Human Intellect, a Conceptual Framework pdf into Google, you will get the link for this and you can then download it and look at it. I’m going to try and explain a couple of the points of view that Doug had and try to explain one of the main ideas.

では、何故、私たちはわざわざエンゲルバートの話をしているのでしょうか? その答えは、1962年に彼が『人間の知性を増強するための概念的枠組み』という提案書を書いたからです。この提案書には、144ページに渡って、パーソナルコンピューティングに関する非常に大きなアイデアが書かれています。ただ、エンゲルバートに関心を持っている人でさえも、これをあえて読もうとはしない人が多いのです。というのは、デモさえ見れば、これを読む必要がないと思ってしまうからです。しかし、実際にはデモで見せられた以上の多くのアイデアがここに入っています。私の今回の講演の目的は、皆さんにぜひこれを読んでいただきたいということです。グーグルで検索していただければ、このPDFをダウンロードすることができます。私はこれから、ダグの提案のポイントをいくつかここで説明します。そして、その中心的なアイデアのひとつを皆さんに伝えたいと思います。

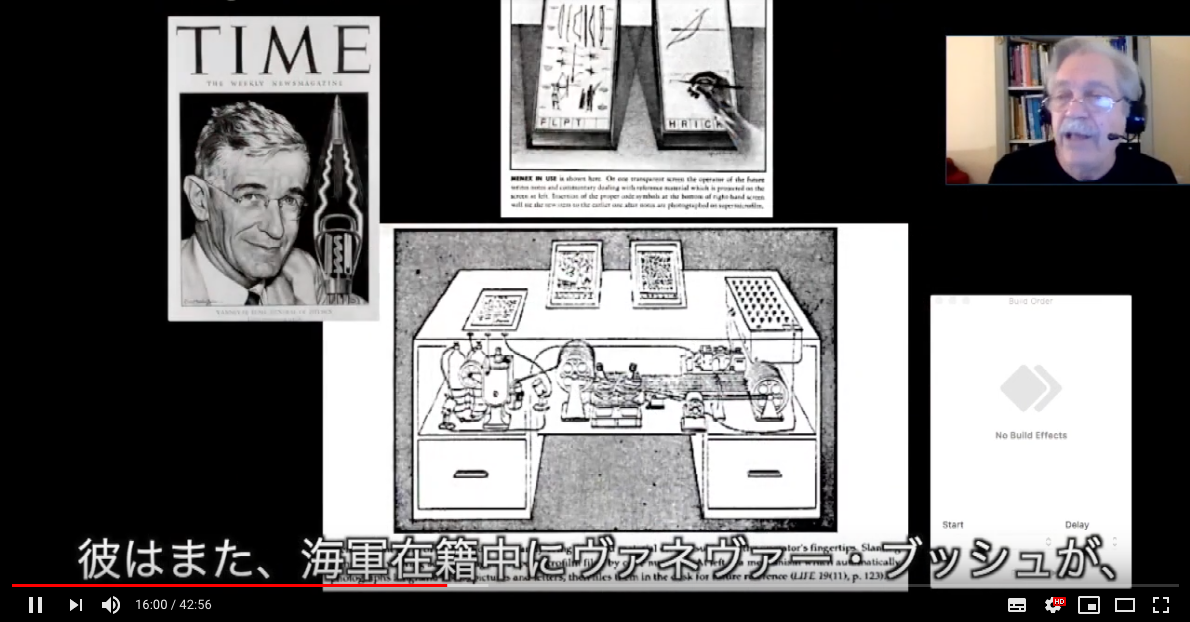

So, to understand this, we have to go back into the 40s when Doug was a young man as a radar technician in the Navy. And it was there that he first saw cathode ray tubes. This was before the age of television for most people. And on these radar scopes, were not just signals, but also symbols. Things like letters and numbers and a general feeling for what the situation was. So, it was a combination of three things. And from that he got the idea very early that machinery in this kind of form could be used to display information.

このアイデアを理解するためには、1940年代まで戻らなければなりません。ダグ・エンゲルバートは、海軍の若きレーダー技術者でした。そこで彼は、初めてブラウン管を見たのです。一般の人々にとってのテレビ時代が来る前のできごとです。そして、レーダーの中では、ただ単に信号だけでなく、文字のような記号、数字、そして、今全体的にどういう状況が起きているかということが表示されていました。これら3つの組み合わせをスクリーン上で見たことから、ダグ・エンゲルバートはこのような機械が情報を表示することができるということに気づいたわけです。

And while he was in the Navy, he read this article by Vannevar Bush about a proposed system for the future called Memex. It was built into a desk. It had multiple screens. It had a stylus and a pointing device. It had a scanner. It had keyboards. And inside, it had enough optical storage the size of a small town library, about five thousand books worth. And you could find things and you could link things. And the idea of hyperlinks actually goes back to Bush’s article. And that really seized the imagination of Doug Engelbart and many other people who saw this at various times.

I didn’t see this. I was only five years old in 1945. I didn’t see this until 10 years later in the 50s.

彼はまた、海軍在籍中にヴァネヴァー・ブッシュが、MEMEX(記憶拡張装置)という将来の先進的なシステムを提案した論文を読んでいました。これはデスク型をした機械でした。デスクの上には複数のスクリーンがあり、スタイラス・ペンとポインティング・デバイス、スキャナー、キーボードが設置されています。デスクの中には光記録媒体があって、小さな町の図書館くらいの所蔵量、約五千冊分の本を収納できるようになっています。そしてこの中を検索したり、内容をリンクしたりすることができます。つまり、ハイパーリンクの考え方は、ブッシュの論文まで遡ることができるわけです。そして、このアイデアが、ダグ・エンゲルバートをはじめ、その記事に触れた多くの人の想像力をかきたてました。

私は同時代には読んでいませんでした。1945年当時、私は5歳でしたから。10年後、1950年代になって初めて私はこの論文に行き当たったわけです。

And in the 50s, Doug had now as thou out of the Navy and he went to graduate school at Berkeley. And the project there was about 25 students and a couple of professors to build an early digital computer from scratch. And here it is as of 1950. And from this, Doug learned a lot about, not only about how computers work, but he got a much stronger idea of how you could make them do things through programming.

1950年代になると、ダグは海軍を退役して、バークレーの大学院に行きました。25人の学生と数人の教授からなる、初期のデジタル・コンピュータを一から開発するプロジェクトに参加しました。これは1950年代の写真ですが、この当時、ダグは多くのことを学びました。ただ単にコンピュータがどのように動くかといったことだけでなく、どのようにコンピュータを作り、どのようにプログラムをして動かしたらいいかといった、より確固としたアイデアを身につけたのです。

And during this period, we’re in the middle of the Cold War and he just served in military service. And so, he started–he worried about the situation of the world. What is going to happen to the world? And he thought, shouldn’t I start trying to do something to help it. And this was in his mind.

He may have seen this quote by Einstein. “We cannot solve our problems with the same levels of thinking that we use to create them.” So, this is from more than 50 years ago, but I think it’s even more important for us to understand this today.

And the thing that goes along with this statement is, what if our thinking abilities are too weak to understand, us to understand our thinking abilities are weak? So, our politicians in Washington have this problem. They act like they know what they’re doing and so they haven’t gotten to a stage where they realize what their limitations are and what they should do to help their limitations. And so, a good heuristic here is to automatically–the first thing you say is my thinking abilities are weak because I’m a human being. I can hardly think at all. Now, what do I have to do to really understand how weak my thinking capabilities are? That takes a lot of work. You have to learn a lot to understand just how bad you are. And once you do, you can start looking at ways that you might be able to improve your thinking abilities and other people’s.

当時は冷戦真っ只中でした。彼は軍で仕事をしていたということもあり、世界情勢に大変気を揉んでいました。これから先、世界はどうなってしまうのだろう?そして、自分も何か問題を解決する一助になれないだろうかと。

もしかしたら、次のアインシュタインの言葉を見たことがあったのかもしれません。 「問題を引き起こしたのと同じレベルで考えても、その問題を解決することはできない」(アンシュタイン)。 これは50年以上前の言葉ですが、その意味を理解することが今日益々重要になってきていると思います。

この言葉の帰結として言えることとして、私たちの思考能力は物事を理解するには弱すぎるということすら理解できない、ということが挙げられます。ワシントンの政治家たちは、そうした問題を抱えているわけです。彼らは、自分たちは何もかも理解しているのだと言わんばかりにあれこれやっているわけですが、実は彼らは、自分には限界がある理解にも達しておらず、その限界を超えるためになにをしたらよいのかも知らないのです。

ではどうすればいいかというと、まずは「自分は人間なので、思考能力が弱いのだ」と言ってみることです。私はほとんど考えることなどできないと。自分の思考能力が実際どれだけ弱いのかを理解するにはどうしたらよいのでしょうか? そのためにはたくさんのことを学ばなければなりません。しかし、一旦それをやれば、自分自身はもちろん、他の人々の思考力を高められるようになります。

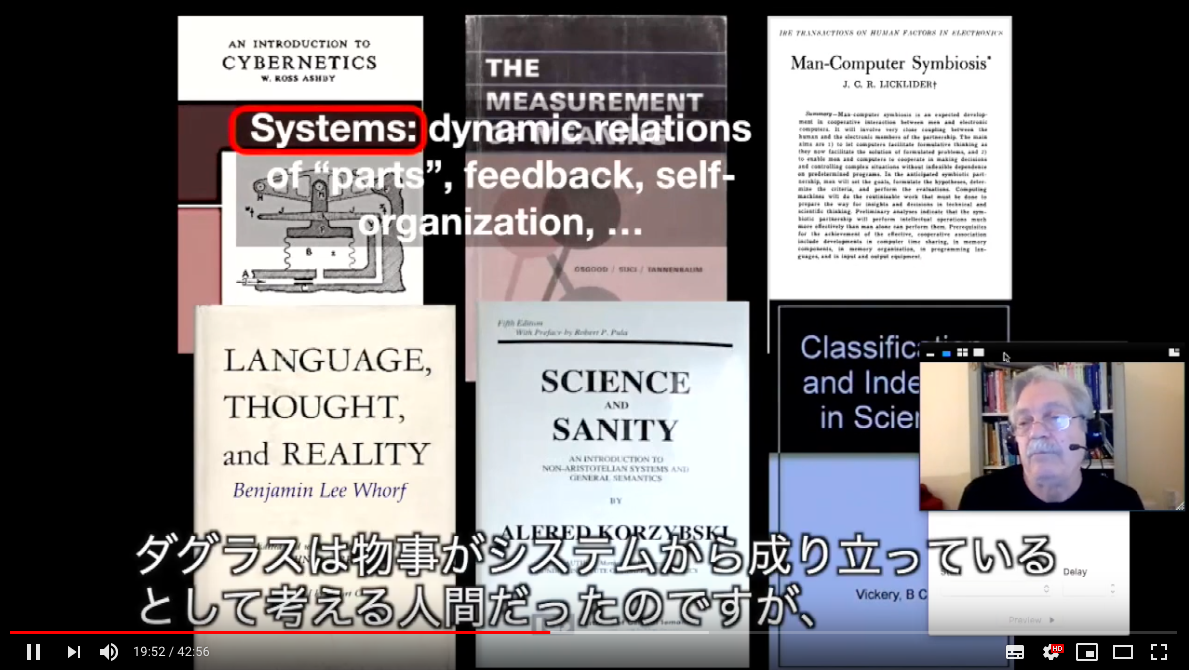

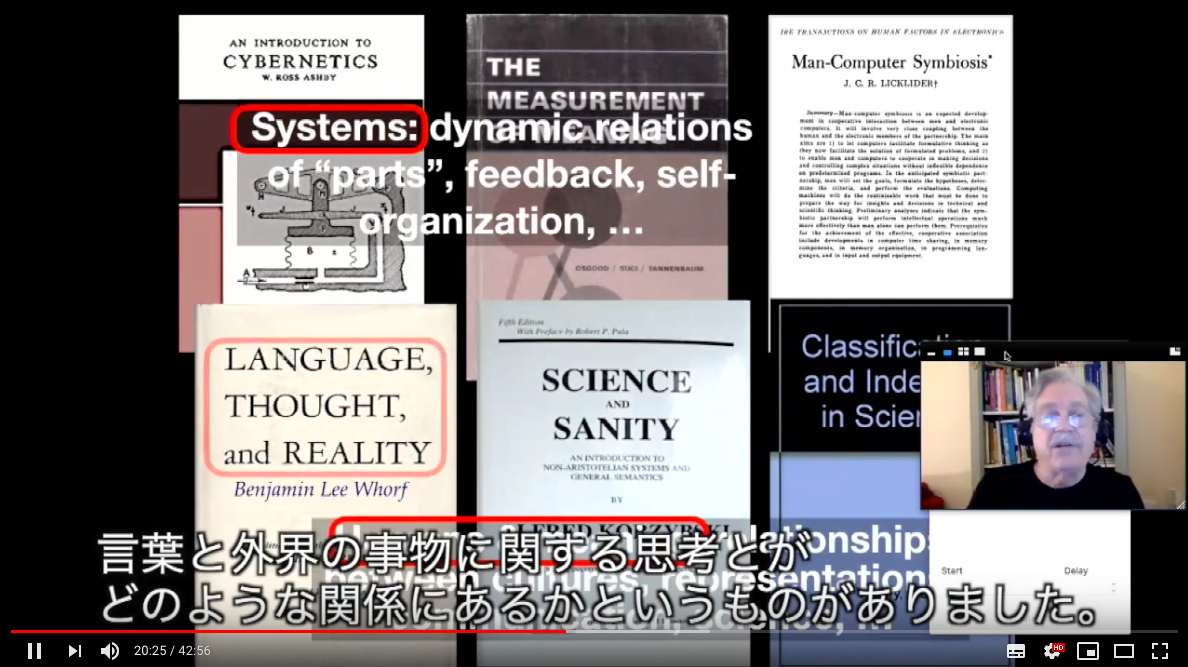

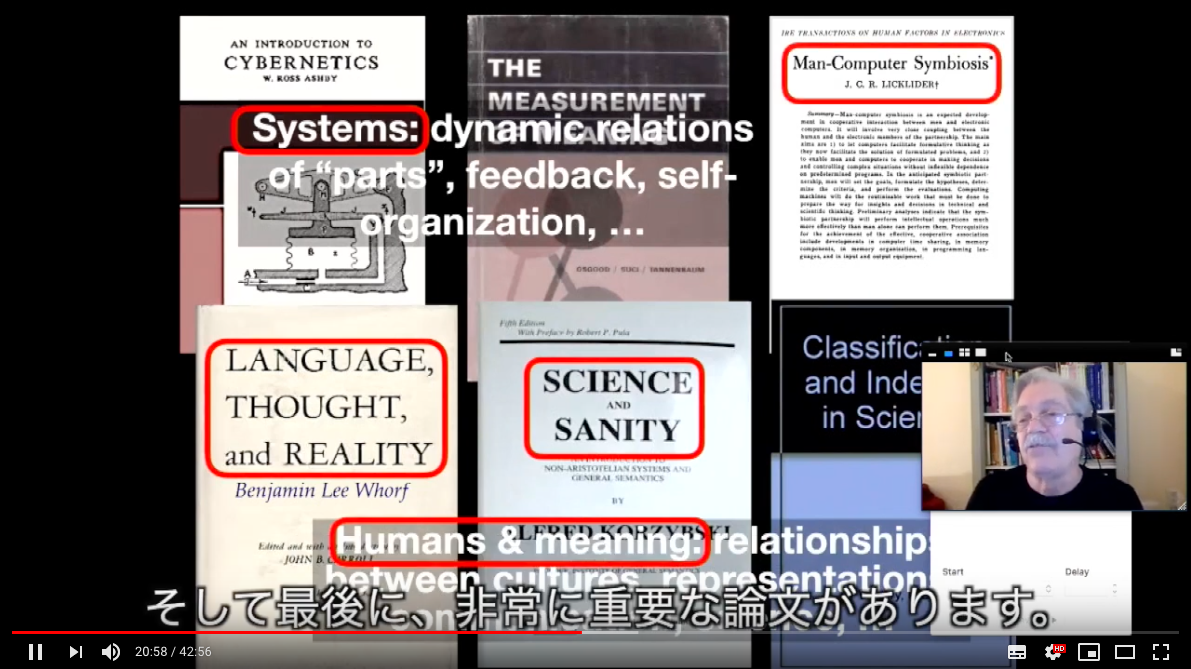

So, one of these ways is to read a lot of books. And these are some of the books that Douglas Engelbart read. So, many of them are about systems. Douglas was a systems guy. He thought in terms of systems and that’s one of the things I’m going to try and explain in a couple of minutes. Because one of the reasons that most people don’t understand what he was driving at is he thought in terms of systems and he tried to explain things in terms of systems.

学ぶための方法のひとつは、本をたくさん読むことです。これらはダグラス・エンゲルバートが読んだ本の一部です。その多くはシステムに関するものです。ダグラスは物事がシステムから成り立っているとして考えるシステム型人間だったのですが、これからの数分で、私は物事をシステムとして考えるということをやってみようと思います。というのも、多くの人たちが彼の本当の意図を理解できない理由は、彼が物事をシステムとして考え、システムとして人々に説明しようとしていたからなのです。

And the other main area that he read in were about human beings and how human beings make meaning in various ways including relationship of language to thought and how we think about what’s out there. And of course, how we think about what’s out there is what science is concerned with. But the map that we have in our head about what’s out there also determines how sane we are. And I think you can see that we aren’t very sane. Our beliefs are in conflict with what science keeps on finding out.

そして、もうひとつ、彼が興味を持って読んだ本の分野には、人類、そして人類が意味を構築するときに、言葉と外界の事物に関する思考とがどのような関係にあるかというものがありました。外界の事物について考えるかということは、いうまでもなく科学が関係することです。私たちが脳の中に持っている外界の地図は、私たちがどのくらい正気であるかということも決定づけています。私たち人類があまり正気ではないということを、あなたは理解できると思います。 なぜなら私たちが素朴に信じることは、科学が発見し続けるものとは相容れないものばかりですから。

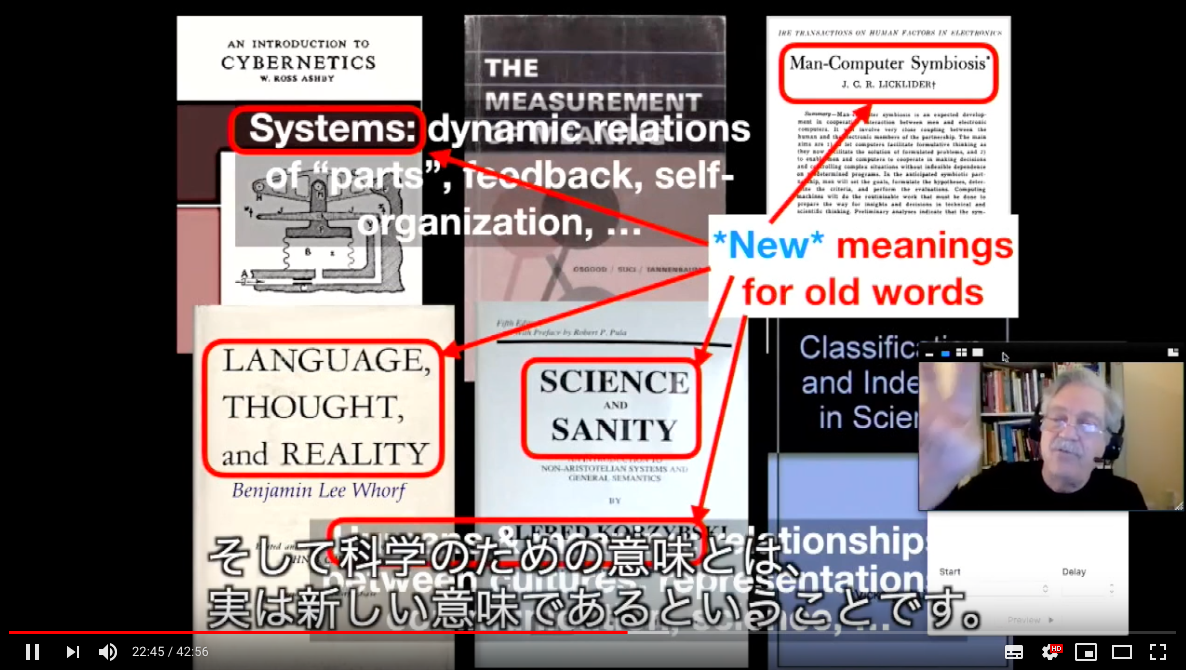

And finally, here is a very important paper which you can also get online, written in 1960 by the person who set up the big funding in the United States that included the funding for Engelbart that developed many of the inventions that we use today. His name was Lickliter, and this was a paper about what it might be like for a partnership between what computers can do and what humans can do and both co-evolving together. Lickliter was a psychologist, so he used the biological term here which is two organisms living in cooperation called symbiosis. And Lickliter predicted that–he said that in a few years, this combination will be able to think like no humans have ever thought before. And, in fact, this turned out to be true but unfortunately just for science and engineering. The extension of this through education into the American and public in the world hasn’t really happened.

Hey, I see Abesahn [phonetic] there. Hey, Abesahn, yay. A great guy. Talk to him later.

そして最後に、非常に重要な論文があります。これもオンラインで手に入れることができます。1960年にアメリカが作った大きな研究基金の設立責任者が書いたものです。エンゲルバートもこの基金から資金を得ており、今私たちが使っている多くのテクノロジーを作るのに使われた基金ということになります。著者の名はリックライダーといい、(『人間とコンピュータの共生』というタイトルの)この論文はコンピュータができることと人間ができることとが協調し共に進化するとどうなるかを考察したものでした。

リックライダーは心理学者だったので、生物学の語彙を使いふたつの個体が共生 (シンビオシス)するという言い方をしました。「コンピュータと人との組み合わせがこれまで誰もなし得なかったような思考ができるようになる、と言ってリックライダーはこのことを予言したわけです。実際には、残念ながら、科学と工学においてはこれが実現しましたが、アメリカにおいても世界においても教育を通じた一般の人々へ普及することはありませんでした。

ハーイ。阿部さんがそこにいますね。こんにちは。阿部さんは、すごい人ですよ。あとで話をしてみてください。

And the other problem with this stuff is that the meanings for systems and the meanings for meanings and the meanings for science are actually new meanings. They don’t mean what most people think they are in standard terms. This is, at least in America, this has confused millions of people. They think they understand what science is but if you haven’t really trained for 10 years and become a scientist, you don’t know what science is. So, if you use the term science, you’re talking about something else. And, in fact, what has happened over the last few hundred years is even the way words are used and what we think of what a word stands for in science has changed.

もうひとつの問題は、システムで使う意味、意味論のための意味、そして科学のための意味とは、実は新しい意味であるということです。これらは人々が思い浮かべる意味ということとは違うものであるいうことです。少なくともアメリカでは、何百万人の人がこのことに混乱しています。彼らは、科学というものが何かということを理解しているとつもりなのですが、科学をちゃんと理解するためには、十年くらいきちんと訓練を受けなければならないわけです。ですから、もし一般の人々が科学という言葉を使ったときは、実際には何か別のものについて話しているわけです。過去数百年を振り返ってみても、単語とは何を代表しているものなのか、どのように使うものなのかということも変化してきています。

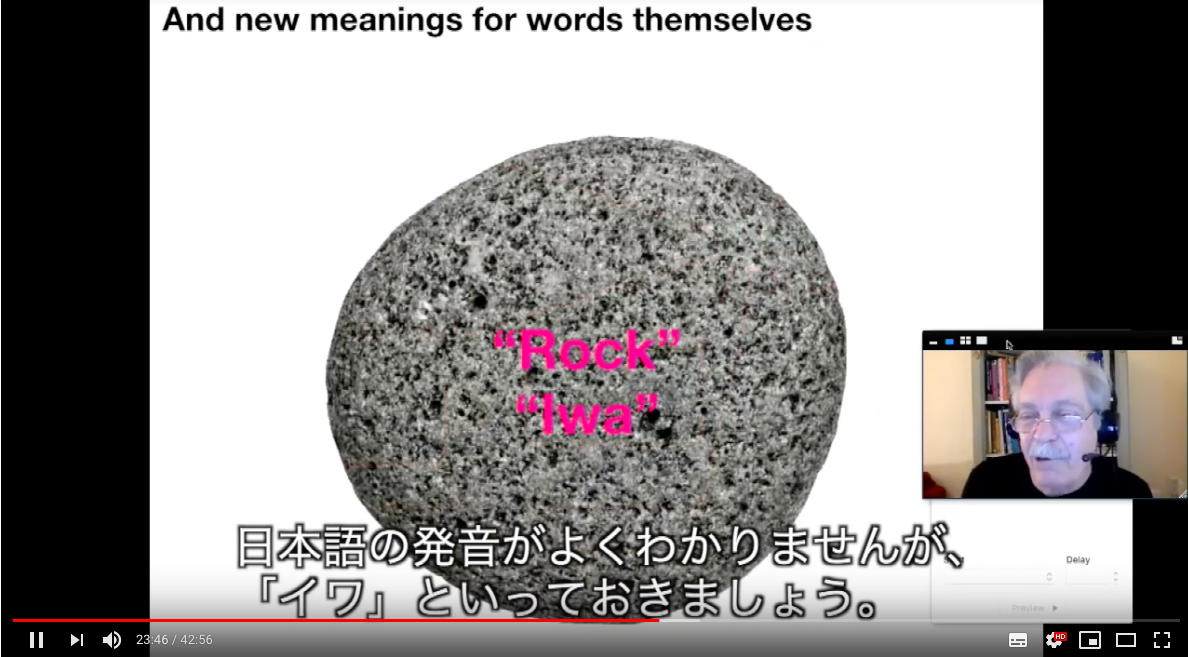

Here’s an example. So, here’s a thing we call a rock in English. “Iwa”, does that work in Japanese? I don’t know what the pronunciation is, but I’ll just say “Iwa.” And it’s a thing. And in English this word not only talks about this specific thing that you can pick up, but it also talks about a class of things called rocks. This draws a kind of boundary around this idea.

一例をあげてみましょう。英語で「Rock」、「岩」ですね。日本語の発音がよくわかりませんが、「イワ」といっておきましょう。ある「何か」です。英語では、この言葉はただ単に「ひとつの岩」という拾って手に持てるものだけではなく、他にも「岩」という種類に含まれるもの、ということも意味します。これは、このアイデアの周りに一種の境界線を描くようなものです。

The word establishes a category. That category excludes things that are outside the thing. So, when you have a thing, you also have not that thing out there. And that is the way that words and thinking in words tends to be used.

That isn’t the way science and modern thinking thinks about it at all because that rock is round. How did it get round? Something must have effected it. It’s actually living in an environment. It has pits in it. How do those pits get in there? Something most have effected it. So, we have this idea that it doesn’t really have a boundary. It extends out and touches things in various ways.

単語はカテゴリを確立し、そのカテゴリは、外側にあるものを除外します。それで、あなたがあるものを持っているというとき、その外側のものは持っていない。言葉の使われ方、言葉を使った考え方は、しばしばこのように(排他的)になりがちです。

一方、科学や現代的な考え方では、このようには捉えていません。なぜなら、この「岩」は丸いけれども、どうして丸くなったのか? 何かからの影響を受けたに違いない。環境内で生きているわけです。どうやって穴ぼこだらけになったのか?何かからの影響を受けたに違いない。つまり、実際には境界線は存在せず、内部のものも外部にまで進出していて、様々な形で接触しあっているわけです。

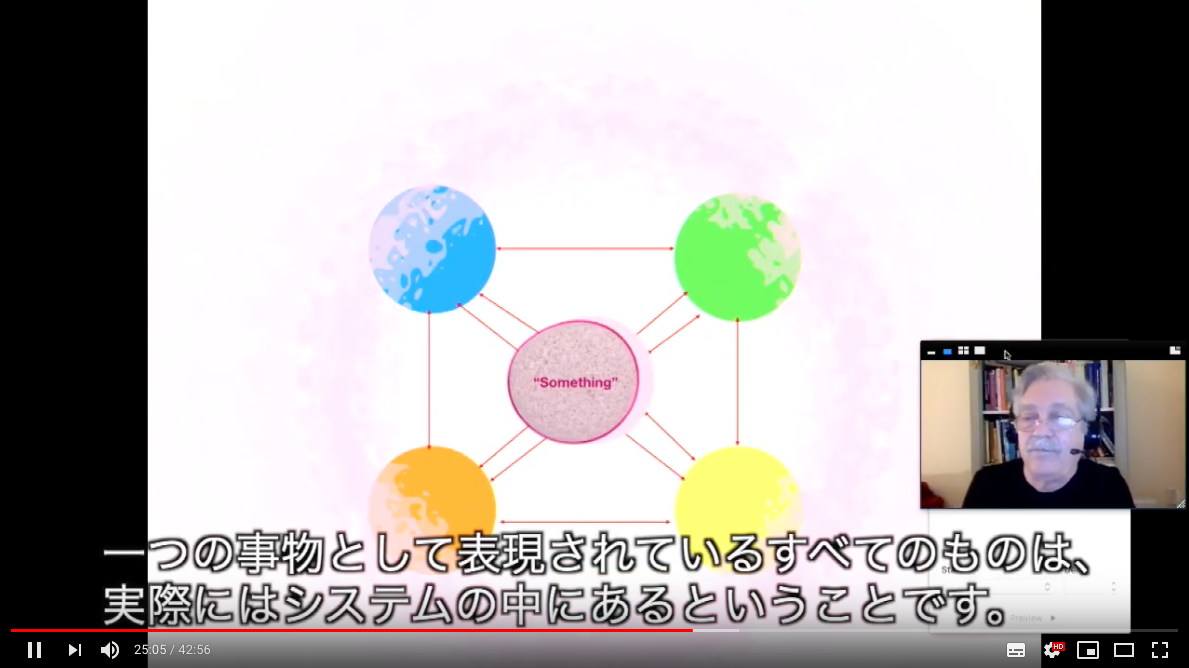

And so, it’s everything that is denoted as a single thing is actually within a system. And you can’t think reasonably about that isolated thing at all. You really have to think about the system. So, this is something that’s best learned in childhood.

さらに言えば、一つの事物として表現されているすべてのものは、実際にはシステムの中にあるということです。そうなると、一つのものだけを分離してしまっては、理にかなった形で考えることができないというになります。真剣にシステムとして考えるなくてはなりません。このことは、子どものうちから学んでおくのが良いことだと思います。

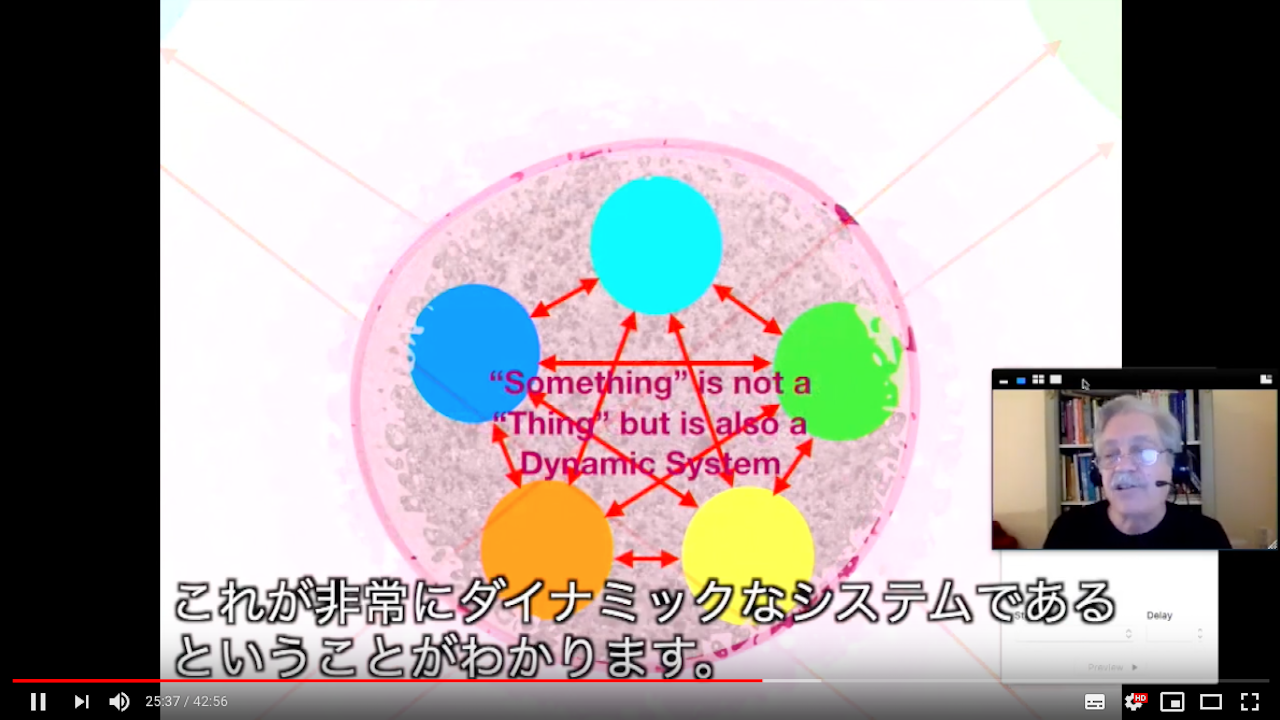

And if we look closer at this thing denoted by a single word, we see it’s also a dynamic system. It’s not just sitting there. Those atoms in there are jiggling around. Things are happening. It’s feeling the outside world and so forth. Now some languages are better at thinking about things as processes than others. English happens to be really bad. It just doesn’t’ think about most nouns as being in process. They just sit there.

So, when Doug thought about things, he thought about them in these terms.

さらに、ひとつの言葉として表現されているものをもっと詳しくみてみると、これが非常にダイナミックなシステムであるということがわかります。静止状態ではないのです。中にある原子は常に動き続けています。常に何かが起きています。外部世界や他のものを感じています。

他の言語と比べて物事をプロセスとして考えやすくなっている言語はあるのですが、英語は最悪の部類でしょう。英語では、ほとんどの名詞は、プロセスとして考えることはできず、ただそこで静止しているわけです。

ダグが物事を考える時は、このようなことを踏まえていたわけです。

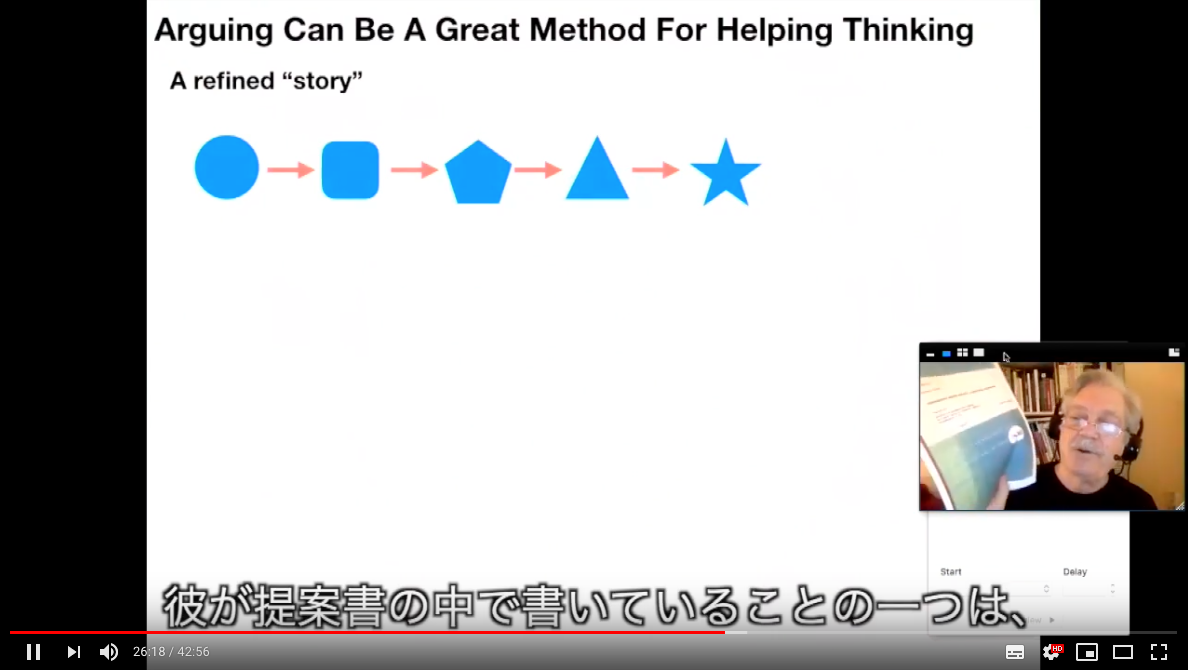

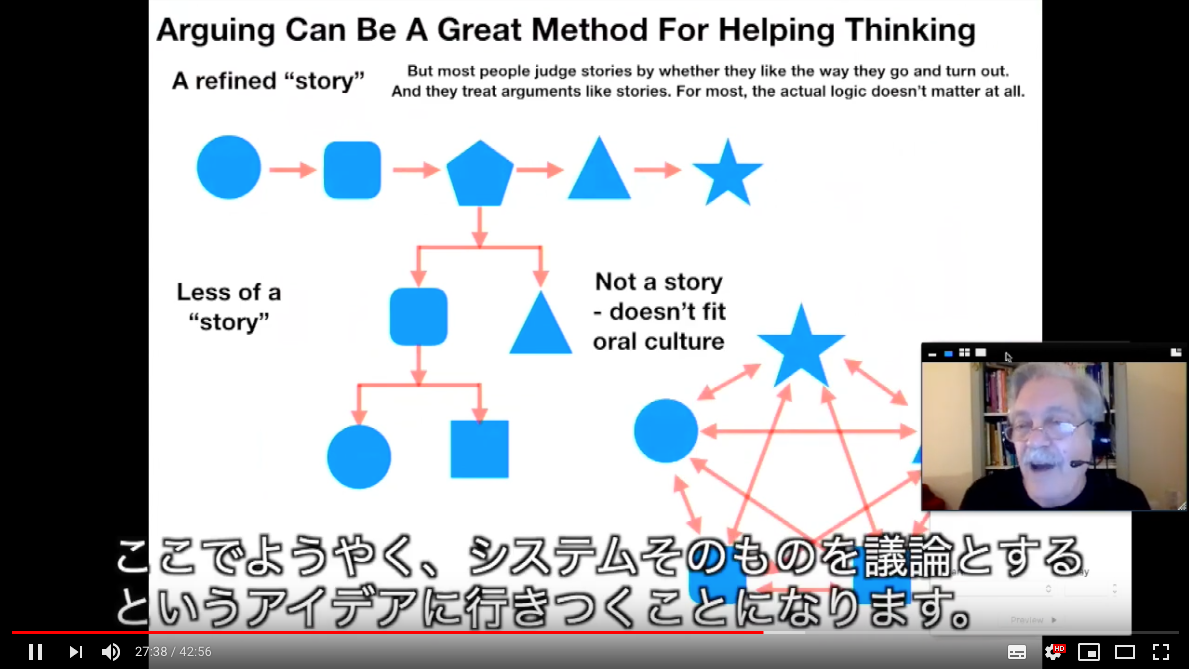

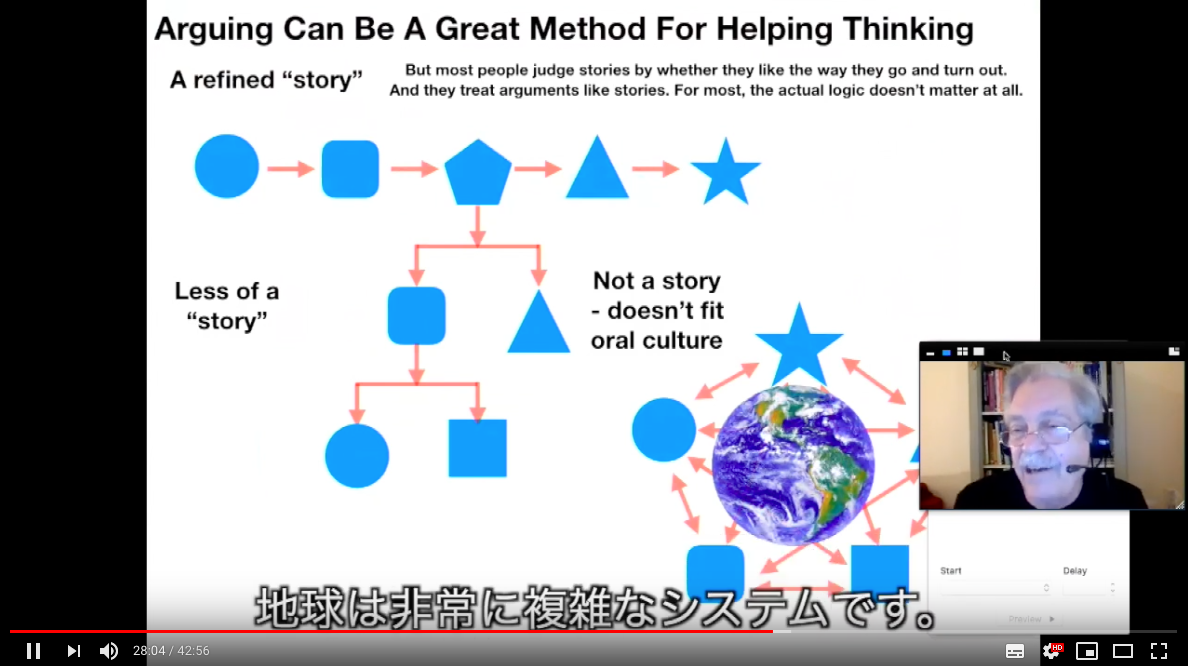

And one of the things that Doug talked about in this proposal was how can we improve our ability to argue in a way that makes progress rather than just trying to win. Because arguing can be a great method to help thinking if we learn how to do it right. And the problem with arguments is that they tend to be like stories. They are sequential, one thing builds on another and there’s a conclusion at the end. And human beings judge stories on whether they like them or not. They don’t care whether they’re true. And if the conclusion of an argument is not what people like, they just dismiss it. It’s like a bad story. I’m not going to believe in that. Like our politicians in Washington and the climate. They just don’t like those conclusions so they’re dismissing it.

And more modern arguments are more complicated. They’re even less of a story. They can have a thing that is supported by many things at once and these things can be incorporated in a more complicated form.

彼が提案書の中で書いていることの一つには、どうすれば、我々の議論能力を改善し、ただ単に議論に勝つというのではなく、建設的な議論をすることができるようになるのか、ということがありました。というのも、議論というのは、正しいやり方を学べば、非常に優れた思考の補助となるからです。議論することの問題点は、話がストーリーのようなものになりがちだというところにあります。直列的な構造になっていて、ひとつのことが次のことの土台となり、最後に結論が来る。こういうストーリーを、人間は好き嫌いで判断します。それが真実かどうかはどうでもいいのです。もし結論が気に入らなければ却下してしまいます。これは悪いストーリーだ。だから私はそれを信じない、と。今のワシントンの政治家と気候変動の話のように。彼らは、結論が気に入らなければ却下してしまうわけです。

現代の議論はもっと複雑で、ストーリーっぽくはないものになっています。ある一つのことが、他の数多くのことに同時に支えられていて、支えている他のもの同士が複雑な構造を取っているというように。

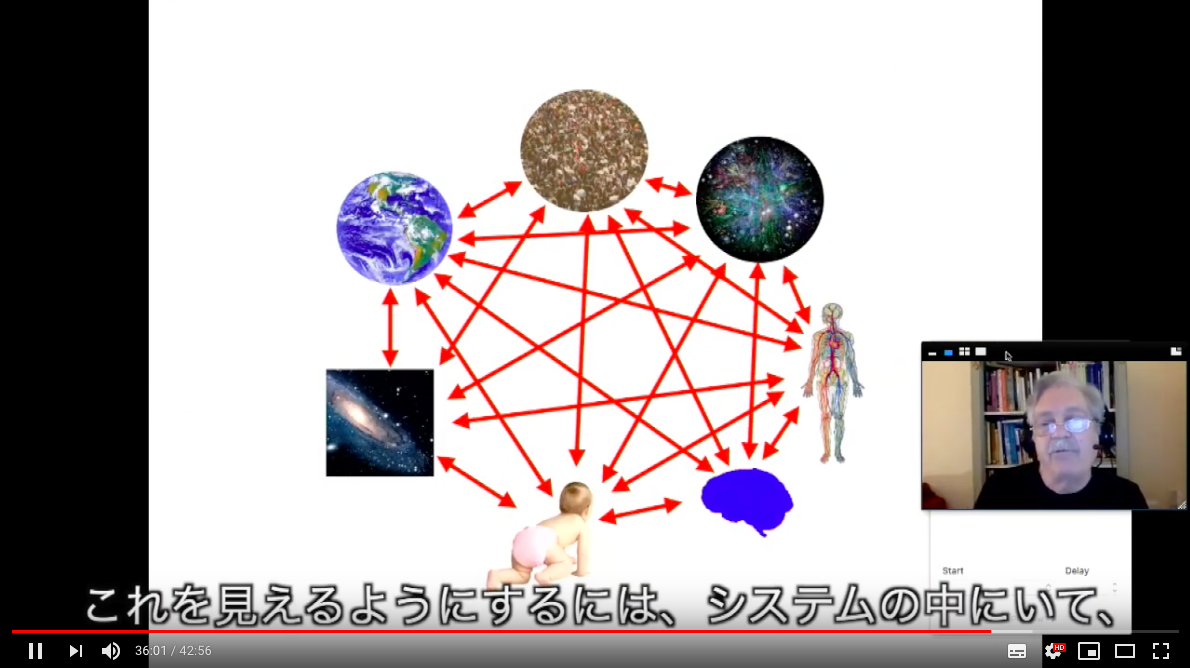

And finally, we get to this idea that a system itself can be an argument. And I can’t give you that argument in a reasonable way in language. Where do I start? It doesn’t have a center. So, this is something where I need something other.

ここでようやく、システムそのものを議論とするというアイデアに行きつくことになります。でもそのような議論は言語では意味のあるやり方で表現できません。どこからはじめたらよいのか? 中心がないですよ?そう思うと何か他のものを用意しなくてはならないようです。

So, for example, what if I want to make an argument about our planet. Our planet is a very complex system. And what I’d like to do is say something about we should probably, we’re probably going to do ourselves in if we don’t pay attention to many systems on the planet that are in danger right now. And there isn’t–the arguments that I see in the papers are about, well this will have economic consequences. Yeah, it’ll have economic consequences, but the problem is actually life itself.

たとえば、私が地球についてある議論をしたいとしたらどうなるでしょうか? 地球は非常に複雑なシステムです。私が主張したいのは、地球にある多くのシステムが危機にさらされており、もしそれらに注意を払わないでいると我々自身が危機に追い込まれるかもしれないということです。しかしながら、私が報告書のようなものでみる議論は、このままでは大きな経済的損失がありますよというようなものです。確かに経済的な影響もありますが、実際はもっと深刻で、人類の生存に関わる問題なのです。

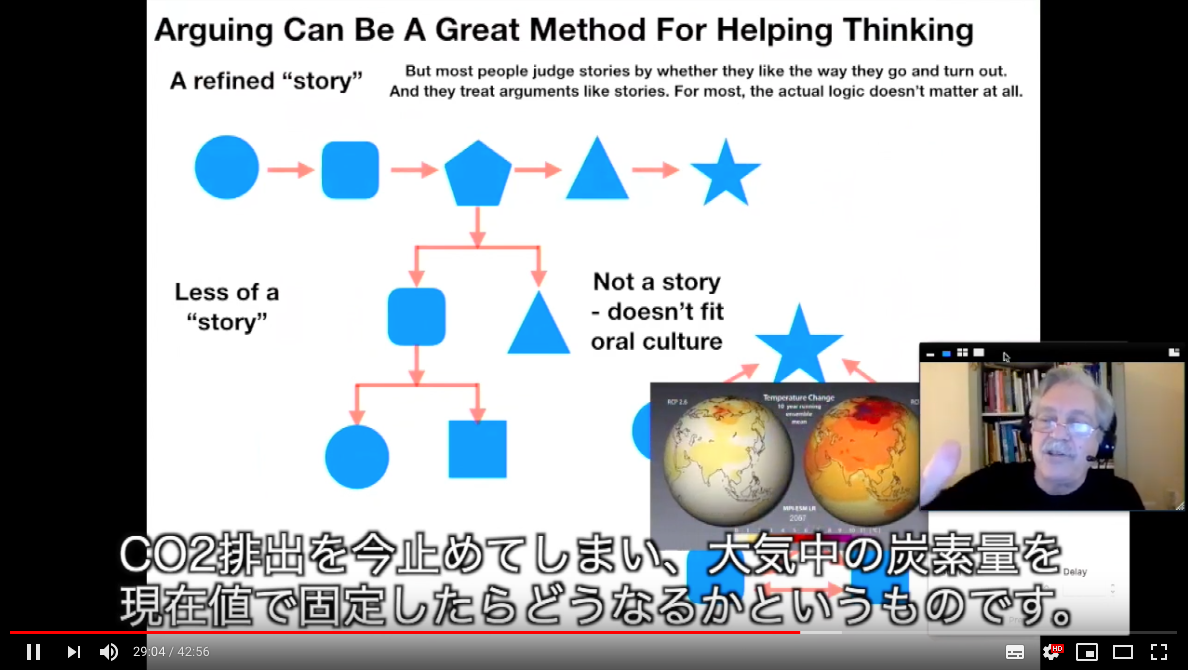

So, here’s an example of a modern argument which is a simulation. So, this is about 100 years of simulation. And the one on the right is what’s going on right now. And the one on the left, this is for temperature change. The one on the left is if we held emissions and the amount of carbon in the atmosphere to what we have right now. So, about 100 years out, this should convince us if we understood what the simulation is based on, that we should probably do something right now. We should treat this as a disaster of the first magnitude and start working on it right now. We don’t want to wait 100 years until the disaster has happened because we can’t put things back together again.

So, to do this for the general public, we need new languages and new tools, new ways of discussing and new ways of arguing. So, these are all part of what Engelbart was thinking about 56 years ago.

これは、シミュレーションを用いた現代的な議論の例です。だいたい100年くらいの地球温暖化のシミュレーションです。右側は実際の状況を示しています。そして、左側のものは、CO2排出を現在で止めてしまい、大気中の炭素量を現在の量で固定したらどうなるかというものです。このシミュレーションの根拠が理解できたとしたら、このシミュレーションで、今すぐ問題に対処しないといけないぞ、と説得できることでしょう。これは未曾有の規模の大災害だ。今すぐとりかからなくては、と。100年間待って実際に災害が起こってから、というわけにはいきません。出てしまったものはもう戻せませんので。一般の人の考えを変えるためには、新しい言語、新しい道具、新しい議論の方法が必要となります。これらは皆、エンゲルバートが56年前から考えていたことの一部なのです。

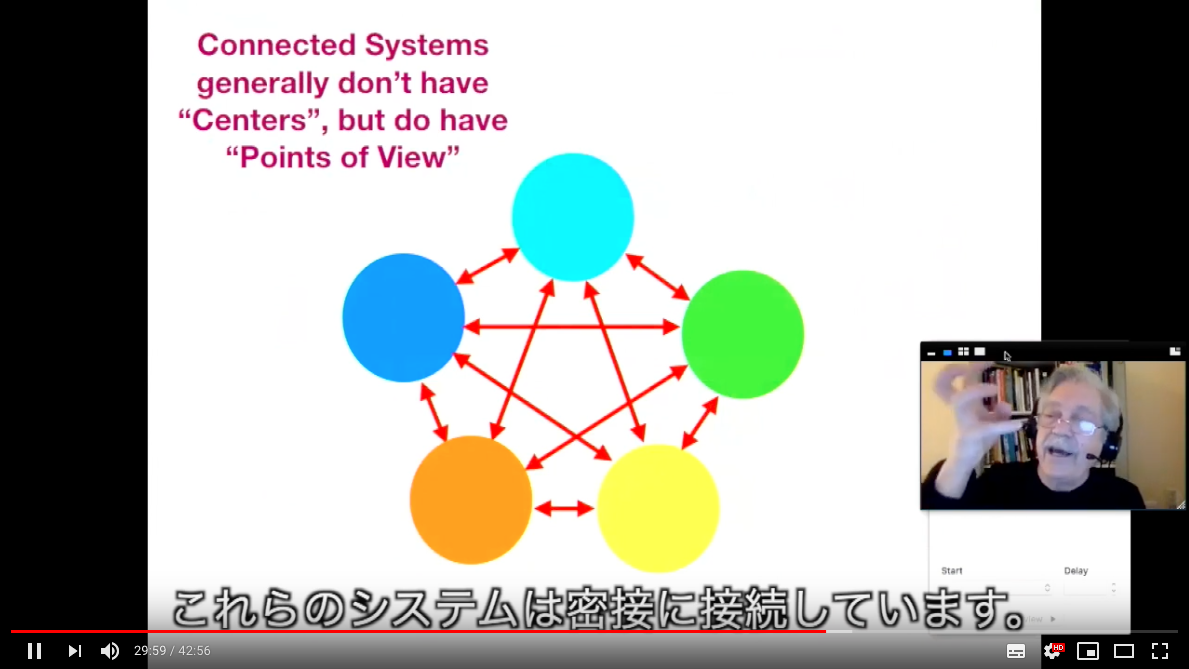

And these systems are very connected. We can go from one thing to another, but we can pick–this has the same connectivity as what I had just a second ago. But I’ve picked one to make it the center and I’m looking at it in terms of all the other things around it. I can use this to help me think about some complicated relationships.

これらのシステムは密接に接続しています。そして、あるシステムから別のシステムへと行き来することができるのですが、このようにその中のひとつに着目して動かすこともできます。こうしても接続関係は、直前までと同じです。しかし、その中のひとつを真ん中に置くことで、そのまわりのシステムとの関係という観点から見ることができます。このようにすることによって、複雑な関係について検討することができます。

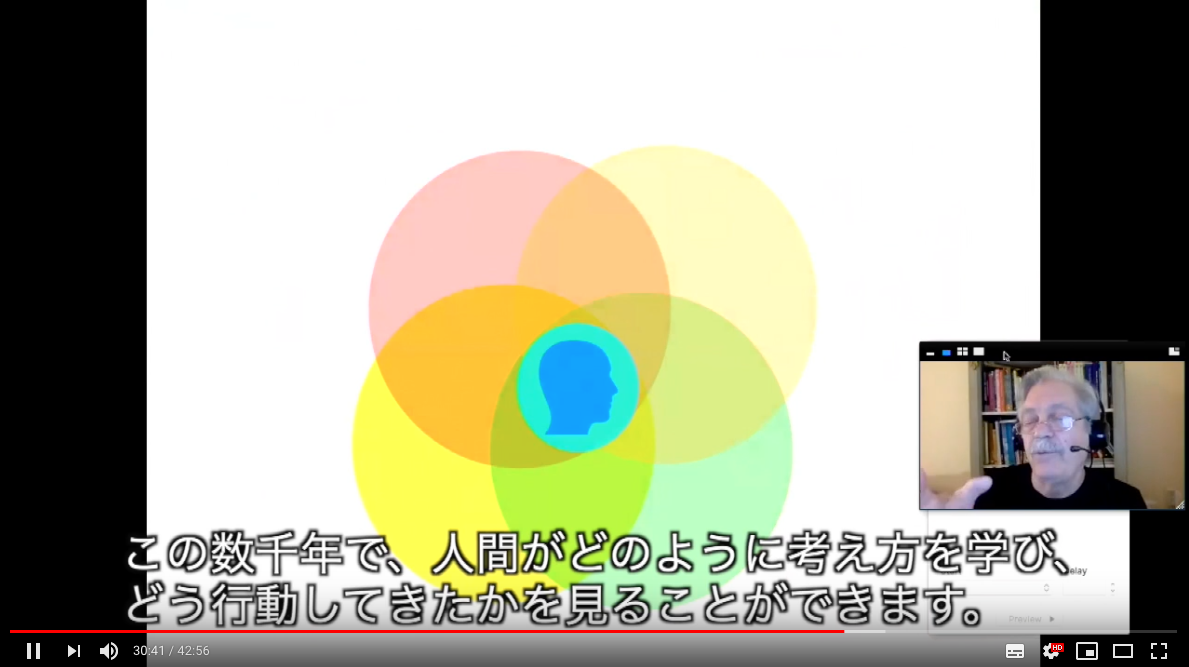

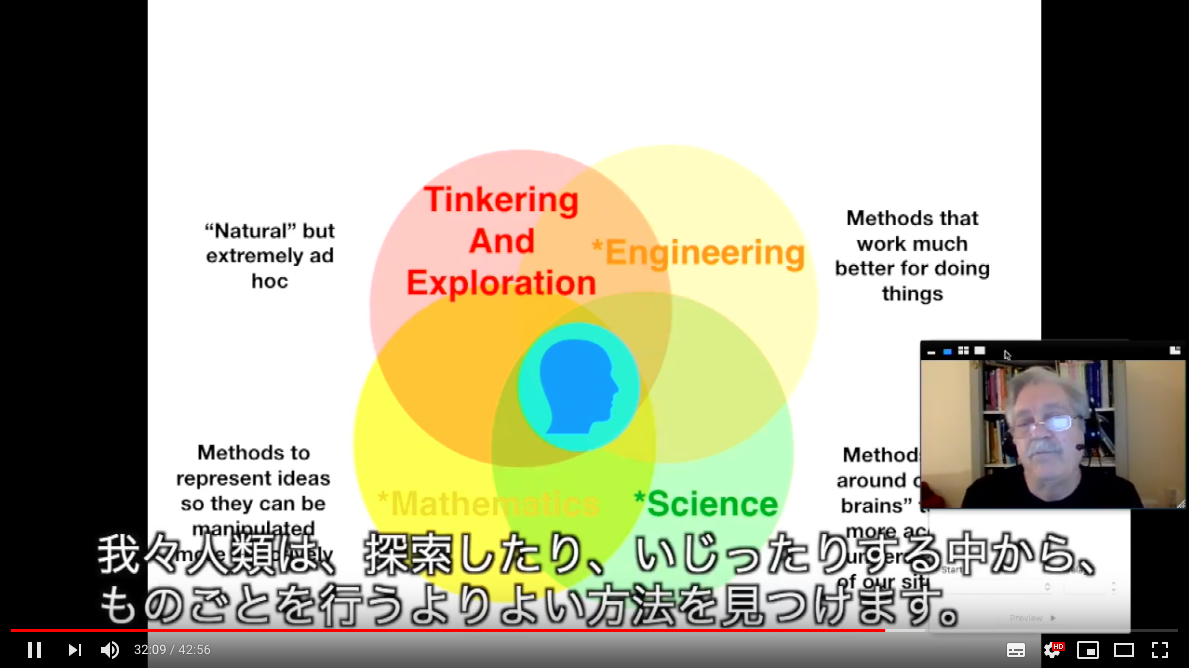

So, for example, here’s another way of looking at this. I’ve changed–made a Venn diagram. I’ve changed the red arrows into overlaps. Let’s just put a human at the center because that’s where we like to be. And we can look at the relationship of how we’ve learned to think and do things over the last thousands of years.

We start out like all animals, tinkering with things; playing around with things; exploring. Mammals do that; monkeys do it; we do it. We can make things, but it’s ad hoc. It’s almost accidental.

But thousands of years ago we invented engineering. And what engineering is all about is to come up with a bunch of methods that work much better for doing some of the things that we’ve, we’ve explored. We don’t know why they all work but it’s like a cookbook in that there are things that, oh yeah, this works better. So, we’ll just, we’ll write this down. We’ll remember it. We’ll pass it on culturally. And engineering led to mathematics as we know it today done a few thousand years ago as part of when the big idea, science, almost got invented. And then did get invented a few hundred years ago.

これは、また別の見方です。集合の重なり合いを示すベン図です。関係を示していた赤い矢印を重なり合いに変更しました。この中心に人間を置いてみましょう。だいたい人間は中心にいたがりますから。そして、この数千年の間に、人間がどのように考え方を学び、どう行動してきたかを見ることができます。最初は、他の動物と同じようなもので、ものをいじったり、遊んだり、探検したりしていました。哺乳類もそうやって行動していますし、猿も同様です。人類はものを作りましたが、場当たり的にやっていました。ほとんどが偶然でした。しかし、数千年前に人類はエンジニアリングを発明しました。エンジニアリングの本質は、人類がやってきた探索をより効果的にできるような手法を作り出すと言うことにあります。一部にはなぜうまく機能するかが説明できない場合もあるのですが、いわば料理本のようなもので、やってみたらうまく行ったからよしとしようと。そのような知識を書きとめ、記憶し、文化的に継承してきたのです。エンジニアリングを通じて、今日につながる数学に発展していきました。同時期に大きなアイデア、すなわち科学もほとんど発明されそうになりましたが、結局は数百年前になるまで待って、科学が本当に発明されることとなりました。

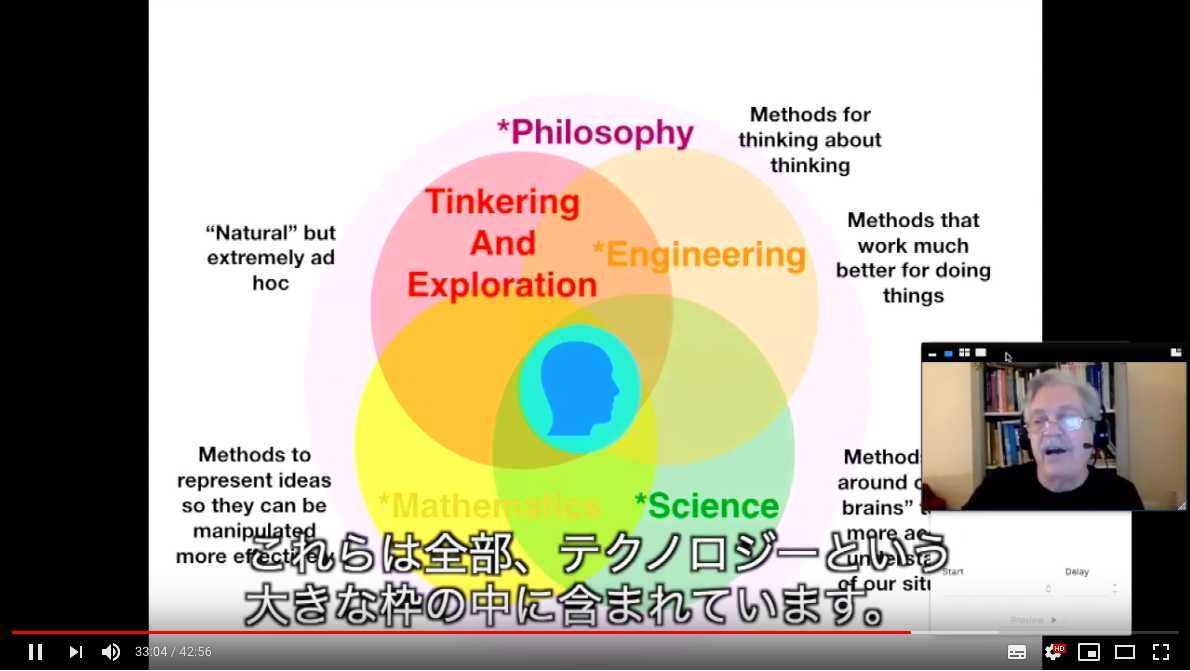

So, if we think about this; we explore; we tinker; we find out better ways for doing things; we represent these ideas so we can manipulate them more effectively. That’s what we’re starting to do with computers now. And science is kind of the master set of methods for getting around what’s wrong with our brains. It’s not–the reason we’re able to find out more about the world using science is because we, we can use scientific methods and scientific instruments for doing things that our brains can’t do. And this idea of philosophy, which is a larger thing. Philosophy is a way of thinking about thinking. And thinking about things that we don’t know how to think about very well.

我々人類は、探索したり、いじったりする中から、ものごとを行うよりよい方法を見つけます。そしてこのようなアイデアを表現することによって、その操作がより効果的にできるようにします。我々は、このことにようやくコンピュータを使いはじめだしたところです。科学は、私たちの頭脳の欠陥を回避するさまざまな方法論の集大成であると言えます。私たちが、科学を使って世界について多くのことを発見できるのは、科学的手法や実験器具を使うことにより、私たちの頭脳だけでは不可能なことを行えるからです。哲学というさらに大きなアイデアもあります。哲学は考えることを考える方法です。私たちが考えるのに向いていない事柄について考えることでもあります。

And all of these things are inside this really large thing called technology. Most people think of technology as something like an iPhone. But technically what technology is is all the things that we make. So, when we make language; when we invent writing and so forth, that’s all technology. So, this is a very, very large area. I’ve put asterisks on technology, philosophy, engineering, mathematics and science because each one of these has a really specific meaning to people who actually do these things. And the meaning is generally a bit different–a lot different–than what the general public thinks of each one of these things. It’s just something to think about here. These are special terms. They really should have new names made up for them.

So, I think we can all see, agree with Doug Engelbart that our most important technologies are the inventions of these things that help us to think.

これらは全部、テクノロジーという大きな枠の中に含まれています。多くの人は、テクノロジーというとiPhoneのようなものだと考えがちです。しかし、テクノロジーというのは、もともと人間が作るものすべてという意味です。言語も書くことも発明されたものでありテクノロジーです。これは非常に大きな領域です。ここで私は、テクノロジー、哲学、エンジニアリング、数学、科学にアスタリスクを付けました。それは、それぞれを実際に行っている人にとって非常に精密な特定の意味を持っているからです。これらの意味は、一般の人々が考えている意味とは少し、あるいは大きく、異なっています。ですから、本当は専門家たちは新しい名前を作るべきでしたね。みなさんも同意できると思いますが、ダグ・エンゲルバートが考えたのは、人類にとって最も重要なテクノロジーは、我々の思考を助けてくれる発明であるということです。

Okay, let’s look at things from the child’s point of view now. Children are not born into nothing. They’re born into a culture. Thousands of years ago, they were born into a hunting and gathering culture. It has thousands of things to learn; it has language; it has stories. And it’s tuned to the brains our genetics make, which are things that are visible; things that are tiny; things that are near us; things that move quickly; things that happen soon; things that involve stories, social matters and so forth. And we see much of this actually operating today.

さて、それでは子供の視点から物事を見てみましょう。子供たちは無から生まれるわけではありません。文化の中で生まれるのです。何千年も前には、狩猟収集文化の中で生まれました。言葉や物語など、学ぶことはたくさんありました。そこで学ぶべきことは遺伝子が作り出す頭脳に合っていました。目に見えるもの、小さなもの、身の回りにあるもの、素早く動くもの、すぐに起こるもの、物語や社会問題に関わるものなど。そして今日でも、この多くが実際に機能しているのがわかります。

But the baby brought up in France is brought up in something that has a few more artifacts, but is very, very simple. It’s very, very similar–except for the artifacts and some of the ideas about how people treat each other–is very, very similar to the hunting and gathering society. That’s still where we kind of are for most of humanity.

So, we’re brought up in a culture, that culture becomes our view of reality. But what are we actually in? What’s invisible here?

しかし、フランスで育った赤ちゃんは、もう少し人工物に接する機会が多くなりますが、それでも非常に単純なものです。人工物があるということ、そして、お互いをどう扱うかということ以外は、狩猟採集社会と非常によく似ているのです。これは、人類全般にわたって言えることです。

私たちは一つの文化の中で育ち、その文化が、私たちの現実に対する見方となるわけです。でも、実際には我々は何の中にいるのでしょうか? 目に見えていないが存在しているというこれは一体なんなのでしょうか?

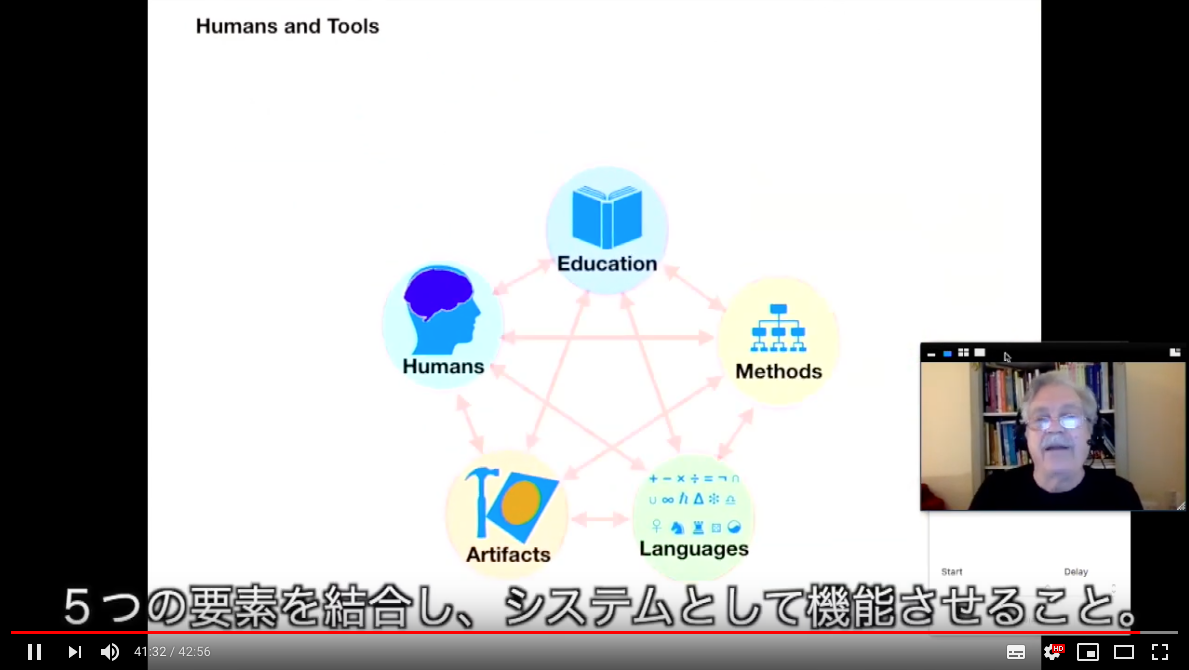

One way of looking at it is we’re in a system of systems and there are 1,2,3,4,5,6 things we should really pay attention to. And this way is kind of difficult for people to look at. So, we can transform this into a composite picture that will give you a better idea.

これを見えるようにするには、私たちはシステムの中にいて、そこには6つの特に注意を払わなくてはならないものがあると考えることです。しかし、この見方は一般の人には難しいかもしれないので、これらを重ね合わせた表現に変えてみます。

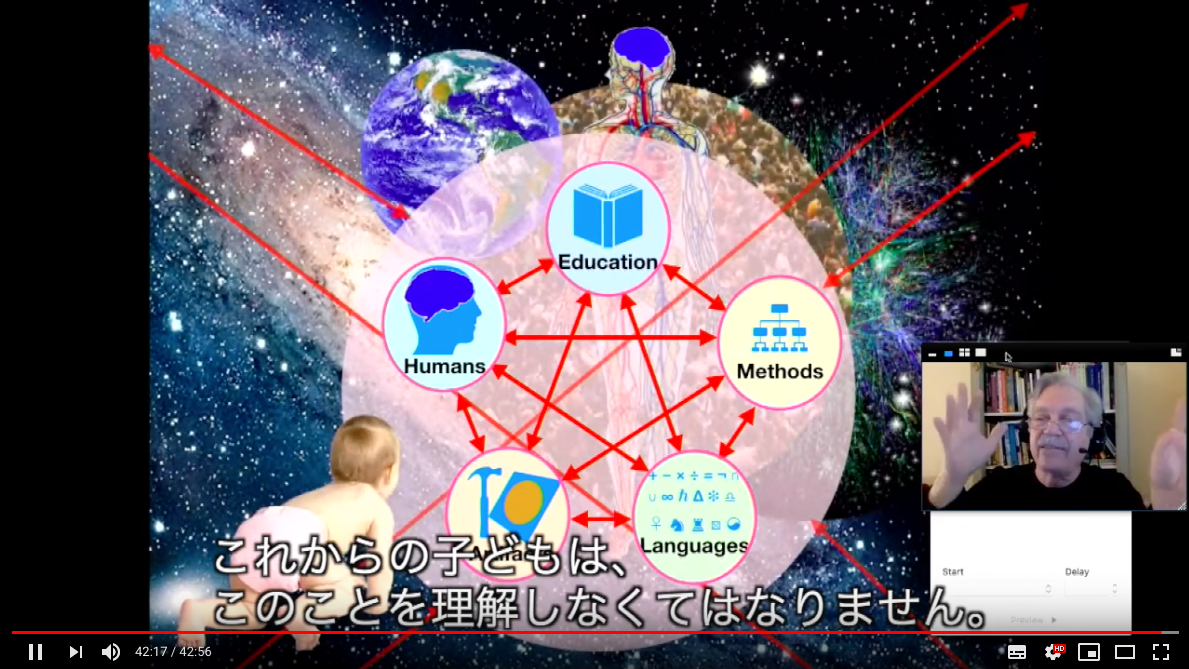

So, the baby is actually being born into a universe, a whole planet–not just their social system but many social systems. Not just what’s around them, but a whole world of technology. This is a self-portrait of the internet, the invisible thing that we’re using right now, but we don’t see. And our bodies themselves are whole systems. And our brains are the most complicated known things in the universe, which are very complicated systems. So, we don’t understand any of these very well yet. And most adults are never going to wind up understanding them because it takes a long time to do it.

So, we want to think about in our program to help the world, we want to think about how can we help children grow up to think better than we can.

赤ちゃんは実際には宇宙そしてとある惑星に生まれ出てくるものす。そして、自分が所属する社会システムの中だけでなく数多くの社会システムの中で生まれ、身の回りにあるテクノロジーだけでなくテクノロジーの世界の中で生まれます。これはインターネットの自画像ですが、これも我々が今まさに利用しているのに目に見えていないものです。我々の人体そのものがシステムです。私たちの脳は既知の宇宙の中で最も複雑なものですが、脳も宇宙もまたどちらも複雑なシステムとなっています。私たちは、これらのどれも理解できていません。そして、ほとんどの大人には理解できないでしょう。これらを理解するには長い時間がかかるからです。

そこで、この会議の目的にあるように、どうすれば世界を助けられるのか、どのようにどうすれば子どもたちが我々よりもうまく物事を考えられるように手助けをできるのかということを考えたいと思います。

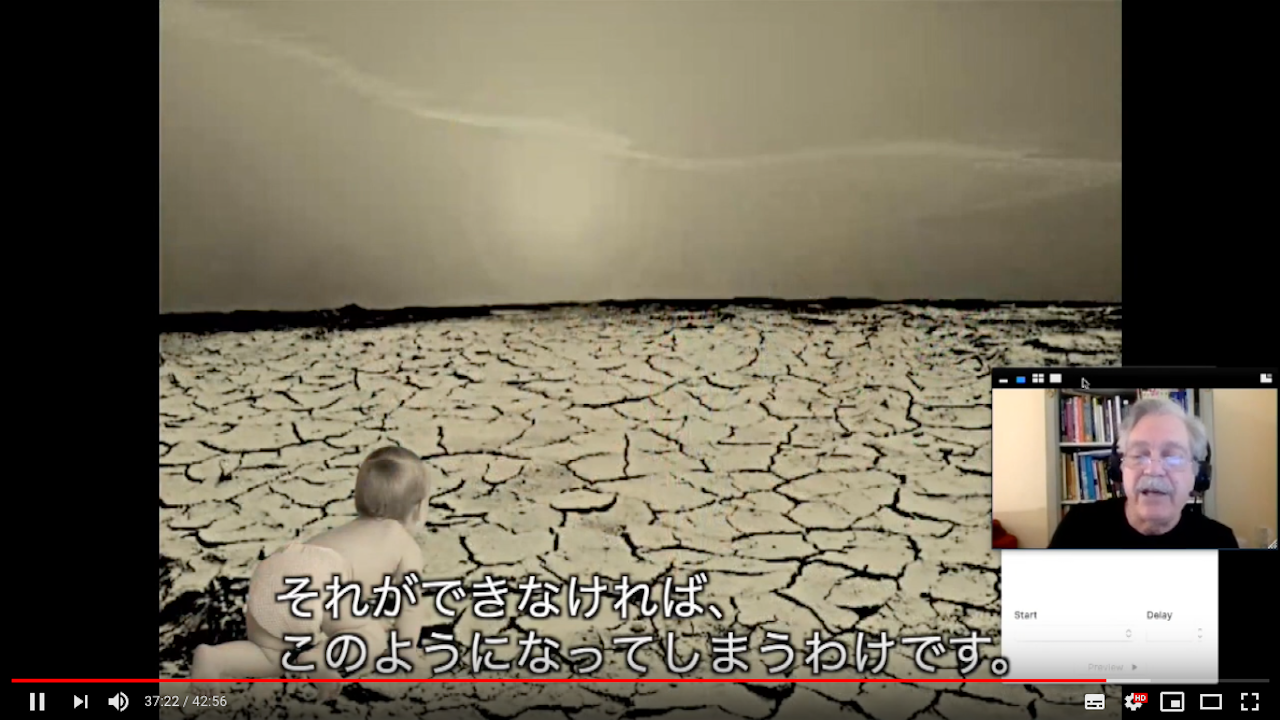

Or we wind up with something like this. So, 60 years ago or so, Doug said, we need to boost our species’ abilities for dealing with complex but important problems. And how can we do that?

それができなければ、この絵のようになってしまうわけです。60年ほど前、ダグは、複雑で重要な問題に対処するためには、人類の能力を高めなければならないと言っていました。そのためにはどうすればいいのでしょうか?

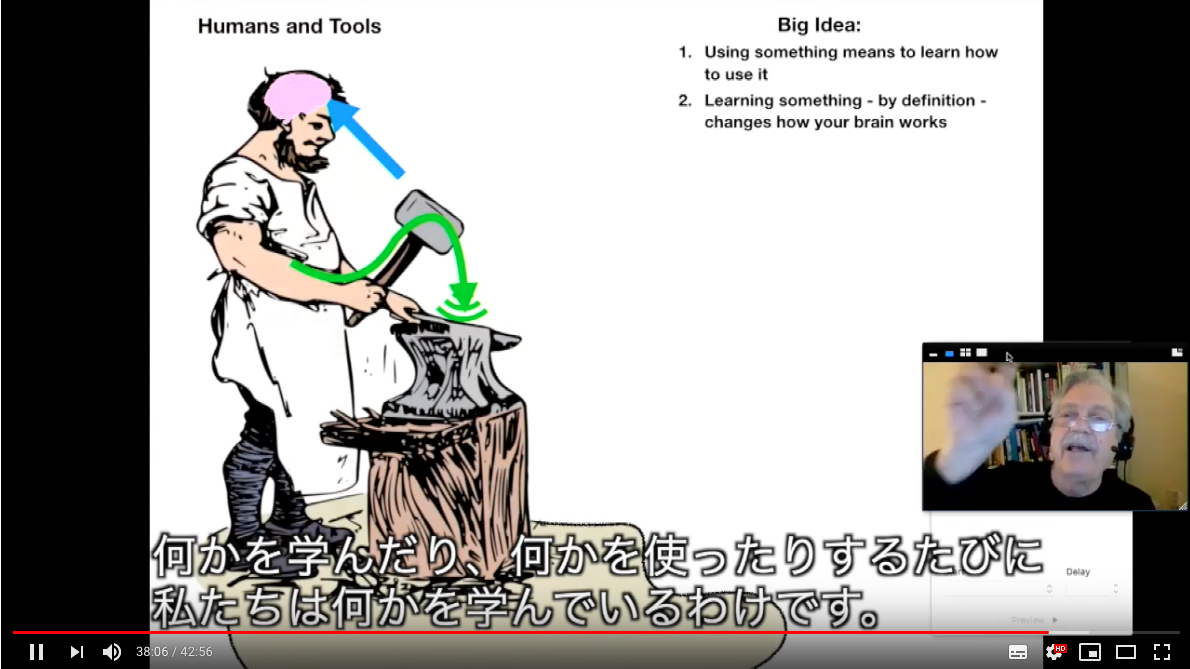

So, let’s look at tools here. The simple way we think about tools are we’ve got it in our hand, and we can do something with it. But by doing that, the tool is doing something to us. We’re learning this tool and when we learn something, when we use something, we learn it. And when we learn something, our brain changes.So, the learning and using of this tool is changing the way we think.That affects how we use the tool and that affects how we change.

まず、道具について考えてみましょう。道具とは何かということに関しては、それを手に持って何かするのに使えるものだと考えるのが分かりやすいでしょう。ただし、使うことによって、道具は私たちにも影響を与えているわけです。道具の使い方を学んでいるわけですし、何かを学んだり、何かを使ったりするたびに私たちは何かを学んでいるわけです。何かを学ぶということは、私たちの脳が変化するということです。つまり、道具の使用が我々の思考に影響を与えます。

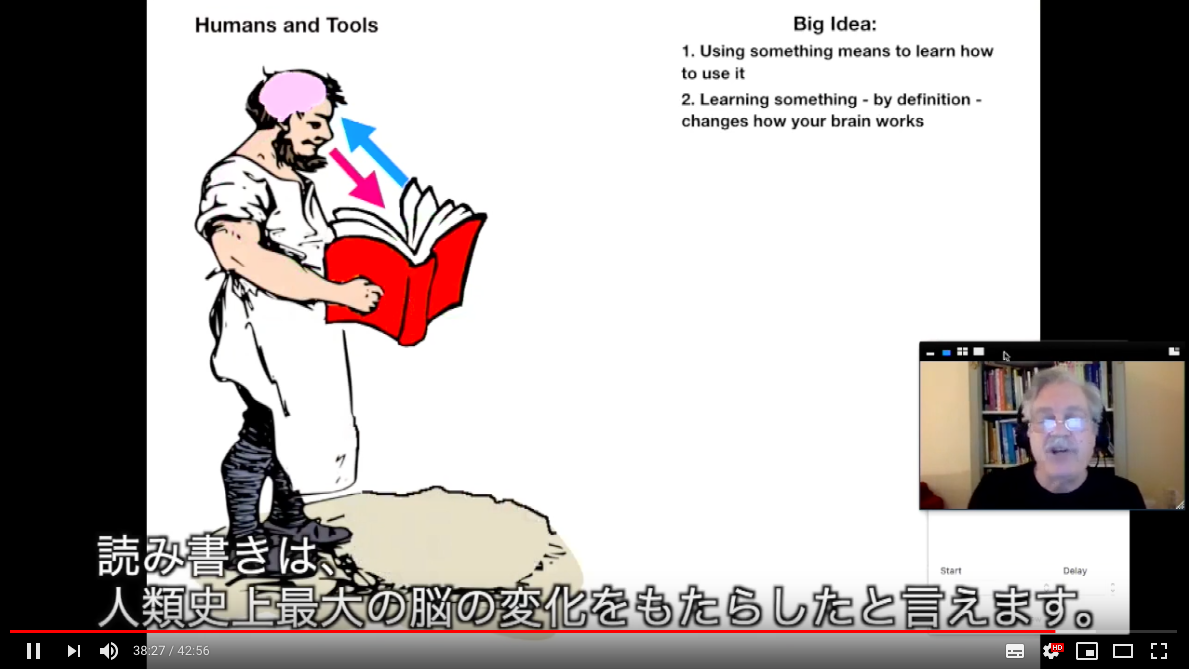

And eventually, we start inventing more sophisticated tools like reading and writing. That was one of the big brain changers of all time because it’s not just about helping us remember. It’s not just about –. It’s about presenting ideas in more powerful ways and learning them in more powerful ways. So, that changed our brains tremendously through cultural learning.

このことが読み書きなどさらに洗練された道具の発明につながったわけです。読み書きは、人類史上最大の脳の変化をもたらしたと言えます。なぜなら、それは単に私たちの記憶を補助したり、時空を超えて通信ができるようになるだけでなく、アイデアをより強力な形で表現したり、より強力な形で学べるものとしたのです。こうしたことを、文化を通じて学ぶことにより、我々の脳は劇的に変化しました。

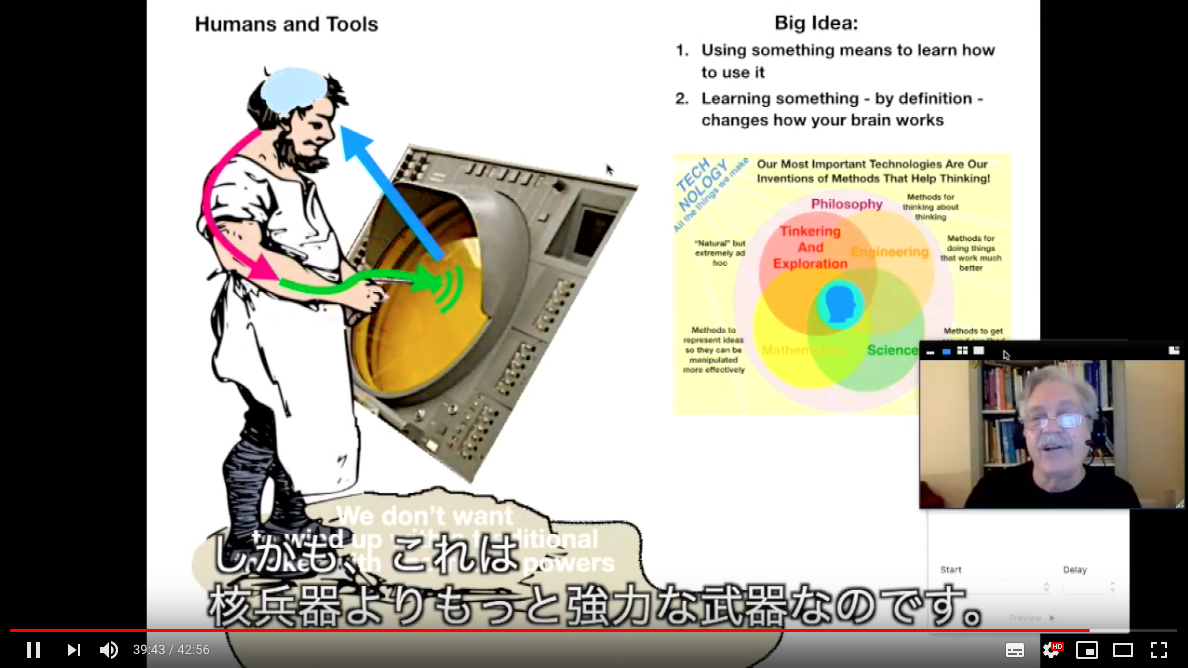

And what Doug asked is what if we gave this person here something that could tap into these powerful recent ideas of the last few hundred years. Like this new interactive computing technology–could that be a good thing?

It’s going to affect us, it’s going to affect us. Can we deal with it? Because we don’t want to give a cave person a nuclear weapon. A rock is okay. They can’t hurt people too much with a rock. But you don’t want to give a cave person a nuclear weapon. And this is more powerful than a nuclear weapon.

And remember what Einstein said. If we take this new power and try to use it with the same levels of thinking that got us into the problems that we’re in, we’re going to make things much, much worse. And, in fact, that is what has been happening in the last 40 years or so since this technology got commercialized.

So, this feedback loop between humans and artifacts is one of the most dangerous feedback loops to set up. And Doug realized that. So, we have to wind up with a new kind of human being or we’ve made things much worse.

そして、こうした経緯に基づいて、ダグは以下のような仮説を投げかけたわけです。もし、人類に、この新しいインタラクティブ・コンピュータ・テクノロジーのような、ここ数百年に渡って得られた新しい強力なアイデアに触れされたら一体どうなるだろうか。それは果たしていいことなのだろうかと。

間違いなく、このテクノロジーは私たちに大きな影響を与えます。私たちは、本当にうまく扱えるのでしょうか。たとえば、私たちは原始人に核兵器を与えたいとは思わないでしょう。岩ならいいです。岩ならそんなに大きな害をもたらしません。でも、核兵器を与えたら大変なことになります。そして、このインタラクティブ・コンピュータ・テクノロジーは核兵器よりもっと強力な武器なのです。

アインシュタインの言葉を思い出してください。もし、この力を使ったがために我々が入り込んでしまった問題を解決しようとするときに、問題を引き起こしたときと同じ思考レベルでこれを使おうとしてしまったら、事態はさらに悪い方向に進んでしまうでしょう。まさにこのことが、ここ四十年間、このテクノロジーが商用化されてからずっと起きていることなのです。人類とこのテクノロジーの間のフィードバックループは一番危険な種類のフィードバックループです。

ダグはその危険性に気づいていました。新たな種類の人類として進歩していかないと、問題をさらに悪くしてしまうだけだと。

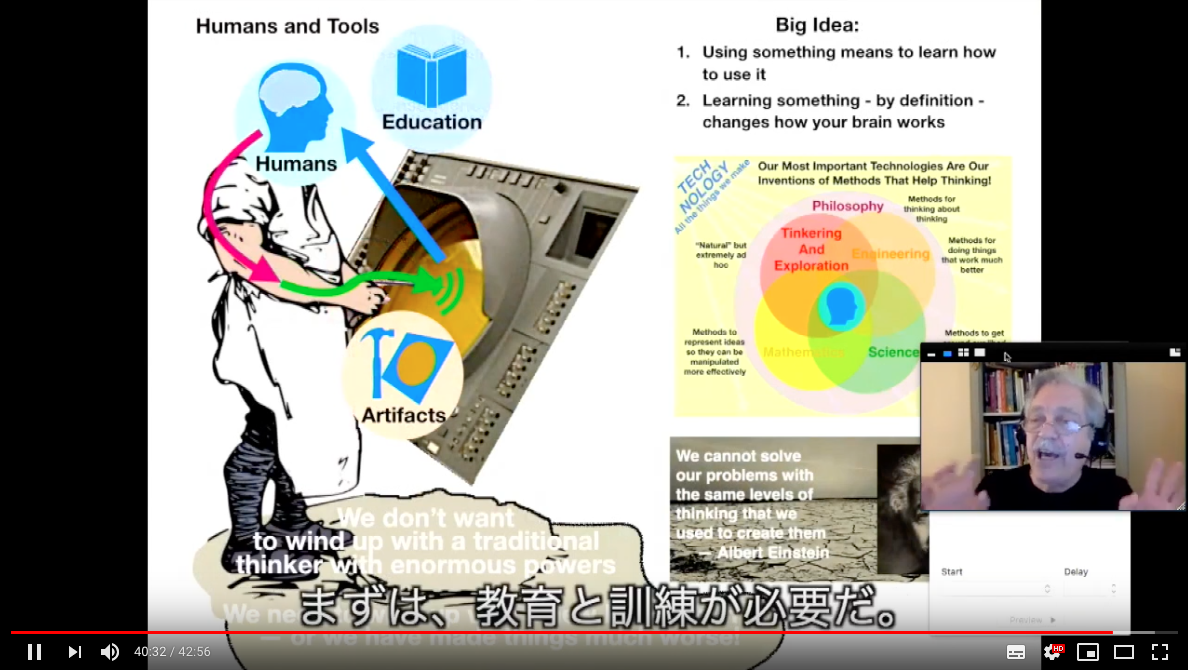

And so, here’s what Doug proposed. He said, look, we need education and training. Do not let anybody use this stuff casually, like people use their iPhones and their laptops. It’s not a casual thing. You can do casual things on it but the effect of it is not casual. The effect of it is enormous. And the problem with tools is that they are terrible teachers. So, we need methods, new methods, like I’ve been talking about. We need new languages, the languages of systems; the languages of science. So, we wind up with five things as a system here. And now those five things together will give us a much better brain than the one we get from just doing a death spiral with technology.

これに対するダグの提案は以下のようなものでした。まずは、教育と訓練が必要だ。これは気軽に使わせてはならない。例えば、人々がスマートフォンやパソコンを使っているようには。気軽に使えるようには作られていますが、それが及ぼす影響は決して気軽なものではありません。とても深刻なものです。また、これらの道具がひどい教師だということが大きな問題です。ですから、これまでお話ししてきたような方法論、新しい方法論が必要なのです。新しい言語、システムの言語、科学の言語が必要です。これで、人間、教育、メソッド、言語、道具の5つの要素それぞれがシステムとして浮かび出てきました。そして、こうして5つの要素を一つのシステムとして扱うことで、テクノロジーの死のスパイラルを続けるだけの頭脳よりも、はるかに優れた頭脳を手に入れられることでしょう。

Okay? So, if we put that into a system here and connect it up, here’s one of the proposals in this 144 pages of ideas. We need to make amplifiers. The computer is one of the greatest amplifiers ever invented. But we must not put it out in a general way without teaching about it, without new languages and new ways to use it. We need larger perspective to think about it. And again, like every system, it is connected to other things. It’s not just an isolated thing.

この5つの要素を結合し、システムとして機能させること。それが、この144ページの論文が提案していることのひとつなのです。私たちは増幅器を作らなくてはいけません。コンピュータはこれまで発明された中でも最も優れた増幅器のひとつです。しかし、私たちは、決してこのコンピュータ・テクノロジーを、新しい方法論や新しい言語を教えないまま、一般に広めてはいけないのです。私たちは、より大きな視野でこの問題を考えなければなりません。繰り返しになりますが、どんなシステムでもそうであるように、このことは他のものともすべて関連しています。孤立して存在しているわけではないのです。

And, in fact, it’s the thing that the child needs to have to understand this, these systems we live in and the systems that we are.

これからの子どもは、このことを理解しなくてはなりません。つまり、私たちがシステムの中で生きているということ、そして、私たち自身がシステムであるということです。

Okay. So, my goal for this talk was to get you to want to go online and get this and read it. Did I succeed? If I did, type this into Google and you’ll get it. And thank you for listening to me.

ということで、私の今日の話の目的は、オンラインでこれをダウンロードして読んでほしいということだったのですが、みなさん、私は目的を達成することができましたでしょうか?もし、そうであれば、グーグルで「人間の知性を増強するための概念的枠組み」と検索して、これを読んでください。

ご静聴ありがとうございました。